A Final Restart?

I’m currently locked out of my bathroom.

The locksmith is an hour or so away, familiar with where I live and what he needs to do, because he solved the same problem yesterday. It’s early morning so my black coffee must do as an anti-bacterial mouthwash for now.

Nothing like a sloppy start to life in a new city.

After spending almost a year meandering around Maharashtra, Pune seems like a city with the right balance — just the right amount of hustle and bustle, and cheaper than the other urban behemoths.

It should be my home for now. Or for a while. Hopefully for a long time. And that is important because ever since I decided to quit New York and Corporate America some four years ago, there has never been this amount of certainty about staying put in one city.

The last few years have been full of restarts. Life was condensed into a large enough suitcase, and then it was time to hop around the globe, one continent at a time. That suitcase was the only physical constant.

Even though these restarts took place in different parts of the world, the pattern of adaptation was similar — find an apartment, make sure it has good internet, find a place to play football and find the courage to make new friends so you don’t feel alone and miserable.

And then, just when there is an inkling of rhythm and comfort, it is time to pack that suitcase up again and move. This happened so often that towards the end I stopped fully unpacking my suitcase. Why bother.

But amidst all this uprooting, I found constant opportunities to purge and cleanse. Starting afresh in a new country meant that I had a clean slate of sorts. I tried to weed out parts of me that I was not proud of while doubling down on those that reaped better relationships, stronger morals and less self-loathe.

I also got a chance to take the best from each culture and hold on to it, even if it seemed strange to the next country. Exposure to a wide range of people and thoughts gave me a level of tolerance and open-mindedness that no book or institute can provide.

But, enough of that.

Real change takes time and commitment. While frolicking around the world is a glamorous luxury I have been fortunate to have, it’s at best only a decent education and at worst, a hedonistic treadmill treading towards perceived, epicurean superiority.

It’s in depth that there is real purpose, real love, real contentment. And for that, it’s important to find stillness — of the mind, of the body, of space.

It’s important to build comfort and familiarity around you so that you can face discomfort that lies at a much deeper level. A level that we are either blind to or that we like to run away from. True purpose lies right there, in that deep-rooted discomfort, where change yearns to be found.

That’s where I’m trying to go.

India, Pune, Aundh is where I will start sowing those seeds, where I’ll unpack my suitcase and put it away until dust can finally find a home on it. Where I hope to stay for as long as it takes to drive the change I wish to see in the systemic injustice that drowns a large proportion of our world.

And I am so friggin’ fortunate to get a chance to do this.

This past year, I have inched closer and closer to figuring out what I want to do. My social enterprise, Ashaya, has started to take shape. I have found a co-founding Chief Scientist to support me in making waste more valuable. The impact ecosystem I have landed into and embraced here in India has been nothing short of encouraging and resourceful. I have reconnected with family that almost competes to shower me with their love and support. I finally have a city and a place that I don’t already have plans to leave from.

So much has happened but I still feel like everything is moving so slowly. I know that the fastest way to make progress is to take your time, but Anish, hurry up already. That’s a constant dilemma I need to continue getting better at handling.

It’s now been a few weeks since I restarted life in Pune. In those few weeks, I have hunted for apartments, found one, moved in, celebrated Diwali in a different town, come back to the new apartment and become best buddies with the security guard downstairs.

I cannot stomach how nice and how large my new apartment is. Will I find the right set of friends? The right internet? The right football league? How long will it take?

Even though I am a seasoned life restart-er, this final restart seems harder than others. Maybe because I’m sick of starting over and over again. Or maybe because this one is for the long haul.

Meanwhile, I am still locked out of my bathroom. The locksmith was supposed to be here a while ago.

I’ll have to call him again.

Aurangabad, Pune, Mumbai, Ups, Downs

Have you heard of the difference between causal reasoning and effectual reasoning?

Well I hadn’t either. But when I did, it gave me that tingly, joyous feeling that resonance beckons. It helped me make sense of the loneliness I had been feeling in the pursuit of entrepreneurship.

Wait, don’t Google it, let me explain.

Aurangabad

I got locked down in Aurangabad. I was supposed to be there for a three-week project, but then the mighty forces of (human) nature had other ideas.

The three weeks quickly became three months, and the illusion of my “plans” swiftly fell through. Nothing is for certain; that is the only certainty.

It was again one of those full circles of sorts. I spent the first nine years of my life living in this little (ish) city. And there I was, some twenty years later, imbibing society-life, like my first memories vaguely remember it.

I was fortunate (again) to be living there comfortably with (another) one of my uncles. For the past few years, the concept of family has always been through the phone — a stray obligation that sprinkles enough guilt to warrant an escape, only for reason to correct course.

But now, in India, it’s family loving through and through. No escape needed, just spoilage. Lots of spoilage, and finally the idea of home is starting to feel real.

It’s been 8 months here since I have been back, trying to start something that addresses man-made injustice. The pandemic has arguably been the only hiccup so far, but I can hardly complain. In fact, it became a reason to engage more immediately in relief efforts.

I worked locally with the organization I had the three-week project with. Their roots across the city allowed us to deliver relief to thousands of homes where relief was needed. And then nationally, we used data to direct donors to the most economically vulnerable states.

It was a whirlwind of pain and hope.

Pain because the pandemic amplified the gap between the fortunate few and the unfortunate many - it suddenly sucks even more to be poor.

Hope because it brought out the best in people. I met people who cared and did, who put themselves aside for a second, who embraced uncertainty to provide an inkling of certainty to those whom certainty refuses to coddle. Humanity, on average, is good. But that doesn’t mean we can’t be better.

This whole ride has been a stark reminder of the need for long-term, systemic solutions to man-made problems. And it was time to refocus on why I was back in India.

Over the last few years, I have worked with several entrepreneurs around the world. They all talked about how lonely the entrepreneurial journey is. I used to just nod along: “yea yea, sure”. But now, for the first time, with a little more skin in the game, I can empathize with them. It’s real. It’s scary. It’s weird.

A month or so ago, I was sure I am going to start up in Aurangabad. I built this sophisticated decision-matrix to figure it out, incorporating the best of reason while dropping in a drop of heart. And I was convinced.

But it’s never that straightforward, is it?

There are so many layers to every decision, so many moving parts streamlined by guardrails, compressed by time, unperturbed by information that exists but hasn’t found you yet.

But what if there are no real guardrails? For instance, I don't have massive amounts of student debt. Or unquenched wanderlust. Or a newborn. I’m in this for the long haul so there’s no real rush to figure it out either, right? I can pretty much be anywhere, and start almost anything.

And what about the doom of objectivity? Objectivity is generally coupled with lucidity. Until you realize that your emotions and personal desires make for a perfectly objective reason. Long haul, remember? The longer I maintain my sanity, the longer I get to work.

All this doom and gloom leads to a swooping epiphany. I am so lucky to have these choices. Because I have invested in such few certainties, I can embrace the wave of uncertainty to push me towards a shore that makes the most sense.

I can’t float around forever obviously, but this floating time is precious. As soon as I make my first investment in something physically certain — office space, a hire — the anchor drops. It’s much harder to re-calibrate then. Most people don’t have so many choices. But maybe sometimes, being spoilt for choice is a valid notion.

So yes, Aurangabad might no longer be where I start up.

Mumbai & Pune

I was in Pune for a couple of weeks for a couple of complicated reasons. But then a connection, a meeting, and suddenly, possibilities abounded, flinging open the doors of a future in Pune that were very much closed. I certainly didn’t see that coming. And no, this is no romantic complication.

In Mumbai now, and this is very much where the heart sits. It reminds me of the best of New York — the hustle, the bustle, the convenience, the people. There also seems to be more of an ecosystem here of like-minded folks doing some version of something similar.

And I finally have my own space. As much as family is awesome, I don’t think I have ever spent this much time with it over the last 13 years. I am used to my space, and that’s one luxury that seems to have become a necessity.

I have spent the last week trying to get settled in as quickly as possible, and that’s exactly when time seems to race. An amazing aunt has lent me her apartment here which I’ve made into an area of isolated comfort. I am focused on productivity and that seems to be ramping up.

But it’s not always hunky dory, I still have so much to figure out about what I want to start. I’m also desperate to just know when I’m going to stop moving — but that is a symptom of luxury that I need to bear.

The mornings are normally full of hope — let’s go, let’s go, let’s go. But during the evenings, when weariness weighs in, everything seems a lot less appealing. The easier path seems so much easier, but never tempting. Because from the get-go, if I wanted to do something easy, I would not be going down this path.

But that doesn’t make the evening hopelessness disappear. In fact, it stings even more — “you signed up for this.” And you feel that just a few more straws and kaput goes the camel’s back.

Back and forth, back and forth it goes.

Causal Versus Effectual

Amidst this cerebral tug of war, there’s always room for an explanation. Understanding the war is half the battle, right? And that’s when Madhukar Shukla’s book dropped in to say hi.

I heard about causal reasoning and effectual reasoning for the first time, and my mind yelled hallelujah. Or eureka. Or something like that when something that’s not your tongue clicks.

Let me quote, because well, we shouldn’t recreate the wheel:

Causal reasoning involves finding the optimal solution to achieve a predetermined goal with a given set of means. The focus is on arriving at a solution which is the most efficient, cheapest or fastest, etc. It is a useful way of approaching a problem when the situation is relatively predictable and the means and ends are more or less clearly defined. Sarasvathy likened causal reasoning to the act of solving a jigsaw problem. Solving a jigsaw puzzle assumes that the perfect picture already exists, and one only needs to find and put the right pieces together in the correct configuration.

(Shukla, Madhukar. Social Entrepreneurship in India (p. 54). SAGE Publications. Kindle Edition.)

Meanwhile:

Unlike causal reasoning, effectual reasoning does not start with precise objectives; rather, it starts with broad possibilities of yet-to-be-made future, and with the means and resources available to the entrepreneur. Entrepreneurs use these to make small experimental beginning, learn from the successes and failures of these steps, identify and co-opt partners, mobilize support and resources in the process, and tweak and modify their goals as they go along

(Shukla, Madhukar. Social Entrepreneurship in India (p. 57). SAGE Publications. Kindle Edition.)

Right?

As much as I think I have my idea all laid out in my head like a massive jigsaw puzzle, it is anything but. I have a vague-ish vision; I have resources and I (seem to) have the will.

Right alongside that is a fog of uncertainty. And the kicker is that the fog must exist. It should only lift as I tread along this path, unraveling permutations and combinations that I can’t even begin to imagine right now.

It’s embracing effectual reasoning, embracing the resources I have to steer towards a direction that makes sense but is not lucid. It will never be lucid, but it’ll almost always be about chasing lucidity.

While that might be true of the macro goal, the micro is all about causal reasoning. While I don’t know what the final jigsaw puzzle looks like, I can start seeing what the pieces are. And maybe causal reasoning is the way to manage the fruition of those pieces, while holding on to effectual reasoning as a guiding light to the overall vision.

All the while, like we already know, uncertainty will be certain. And uncertainty is almost always the root cause of discomfort.

So it all comes back to that cliched age-old way of being — finding balance while embracing discomfort.

Nice, wow, that was therapeutic, thanks for reading. Hopefully, I saved you a Google search.

My “Custom MBA”: Way More For Way Less

I quit the corporate world to pursue purpose in the social impact space. But I knew nothing about social impact.

So, I thought of doing an MBA with a focus on social entrepreneurship. But that just didn’t ring right — how am I going to learn about poverty sitting in a fancy classroom? And expensive much? So, I settled on doing it myself — essentially learning by doing.

In two years, I lived in three countries, worked closely with three organizations and over fifteen social entrepreneurs, learnt a new lenguaje, learnt how to code, earned board seats on two non-profits, built a deep, meaningful network with a plethora of people across borders, made the best of friends immersing myself in cultures inertly foreign, and most importantly, I learnt about the social impact space by living and working in the field.

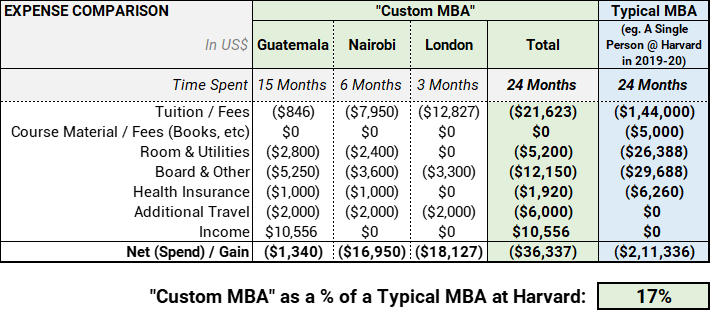

And the kicker? All this cost me less than 1/5th of what a top two-year MBA school would cost. Yes, I did the math. A two-year MBA from Harvard in 2019 cost $211,336 and my two year “custom MBA” cost me $36,337 (scroll to the end for a summary and I also breakdown expenses in each country throughout this post).

Yes, with the COVID-19 pandemic, things seem different and strange right now. But I believe it will pass, and borders will open. It will probably never be the same, but we will embrace a new version of normal that isn’t too different from how it used to be.

So, was this “custom MBA” a better option than doing a traditional top-tier MBA? I’d like to think so. But I have incomplete information — I haven’t done an MBA now have I? So, I’ll let you decide once you’ve read through this.

Here’s how it flowed — resources, expenses, learnings, pains, joys:

The “Plan”

Right when I quit, I knew I wanted to go back to India to start my own social enterprise focused on poverty. However, the tug-of-war in my brain was this:

Should I go to India right away and learn by doing work there? Or should I frolic around the developing world, gaining a more worldly perspective on the impact space?

Both options made sense, but the latter resonated with my fancies a bit more.

For some odd, irrational reason, I had always wanted to learn Spanish and see the world from a more immersed perspective than a touristic one. So, that became the rationalization, and this became the chosen, Dharmic path. Only later, while I was in Nairobi, did I read that working in different cultures actually enhances creativity, fueling the development of a holistic perspective that can allow you to make more of an impact. However true you believe that to be, it was perfect for my confirmation bias.

Since I was embarking on this Fogg-ian, country-hopping path, the idealistic version of myself thought it was going to be super simple:

I’ll spend 6 months working in South America learning Spanish, 6 months in Africa because it’s tough out there, 6 months in Asia outside of India because why not, and then 6 months in India because I need to understand India. Simple, right?

This “plan” turned out to be as naïve as it sounds. It changed. A lot.

Or rather, I’d like to think that it evolved, while somehow staying true to its ethos. That’s the beauty of a “custom MBA” — flexibility. You never know the perfect answer right off the bat, what’s crucial is the ability to pivot. And boy did I pivot.

But you know what? It’s okay to have an idealistic plan as long as you’re not too attached to it. In fact an ideal plan allows for course correction.

Stop 1: Xela, Guatemala

The first part of the first part of the plan stayed its course. Kind of.

South America evolved into any developing country where Spanish is spoken. And more importantly, the work I’d be doing needed to align with what I wanted to learn.

So how did I find this magical thing? The internet made everything a lot easier.

My incredible sister pointed me to MovingWorlds.org — it’s essentially a Tinder for matching the skills of professionals / experts with the needs of non-profits / social enterprises around the world. Yes, I know — pretty awesome. Through this platform, I matched and got offers from three organizations — two in Peru and one in Haiti. Almost took one of the ones in Peru.

Another friend pointed me to SocialStarters. They do something similar but charge a hefty amount for it which didn’t sit too well with me. I was looking for a barter between my skills and exposure to the impact space and 600 pounds (1,280 pounds now) seemed a bit on the higher end. But if I got desperate, it could be an option. I spoke to them and they did offer me a spot in Brazil. Good back-up but not cost effective or Spanish enough.

Then there were a bunch of forums and groups that were helpful — Skoll Foundation, Ashoka, Social Enterprise Jobs Google Group.

I struck gold on the Skoll Forum — Alterna, a social enterprise cultivator / accelerator based in Guatemala, made the most sense. I would be getting width: a chance to work with many social entrepreneurs and that seemed like a sensible way to start. And, Spanish of course.

Here was the problem though — I didn’t know much Spanish at all, and this job was in Spanish. Alterna took a leap of faith and interviewed me — I wasn’t going to get paid and my work experience seemed valuable to them. I got the offer with a caveat: I would need to do a month of intensive Spanish classes in Guatemala before I started. Perfecto.

I was pretty sure I was going to get robbed as soon as I landed in Guatemala thanks to all the one-sided data on crime we have available today, and also because my lack of Spanish made me essentially deaf and dumb.

But I didn’t get robbed or murdered. In fact, everyone was super friendly. Guatemala isn’t the safest country in the world, but it isn’t as dangerous as fear makes it out to be.

I thought I would learn enough Spanish studying 5–8 hours a day for a month and living with a local host-family. Wrong again. It took me 4–5 months to be decently functional in Spanish.

And I’m not talking basic Spanish, I’m talking work Spanish. That was the hardest part about Guatemala — learning a new language. On the flip side, the best way to learn a new language is to jump into the deep end.

Enough people spoke English at the company to allow me to add at least some value. And I quickly learnt how invaluably incredibly amazingly awesome Google Translate is. I came there as an unpaid fellow but within three months, I was offered a paying job. In the end, knowledge is language-less.

It was at about the six-month mark that I had just earned enough clout to make a significant impact within the organization. My Spanish started to get in key, and it just didn’t make sense to jump ship right then.

There had been a lot of turnover when I joined and that gave us fellows an opportunity to add real value. At times we were flying blind, but being thoughtful and thorough goes a long way in making a difference.

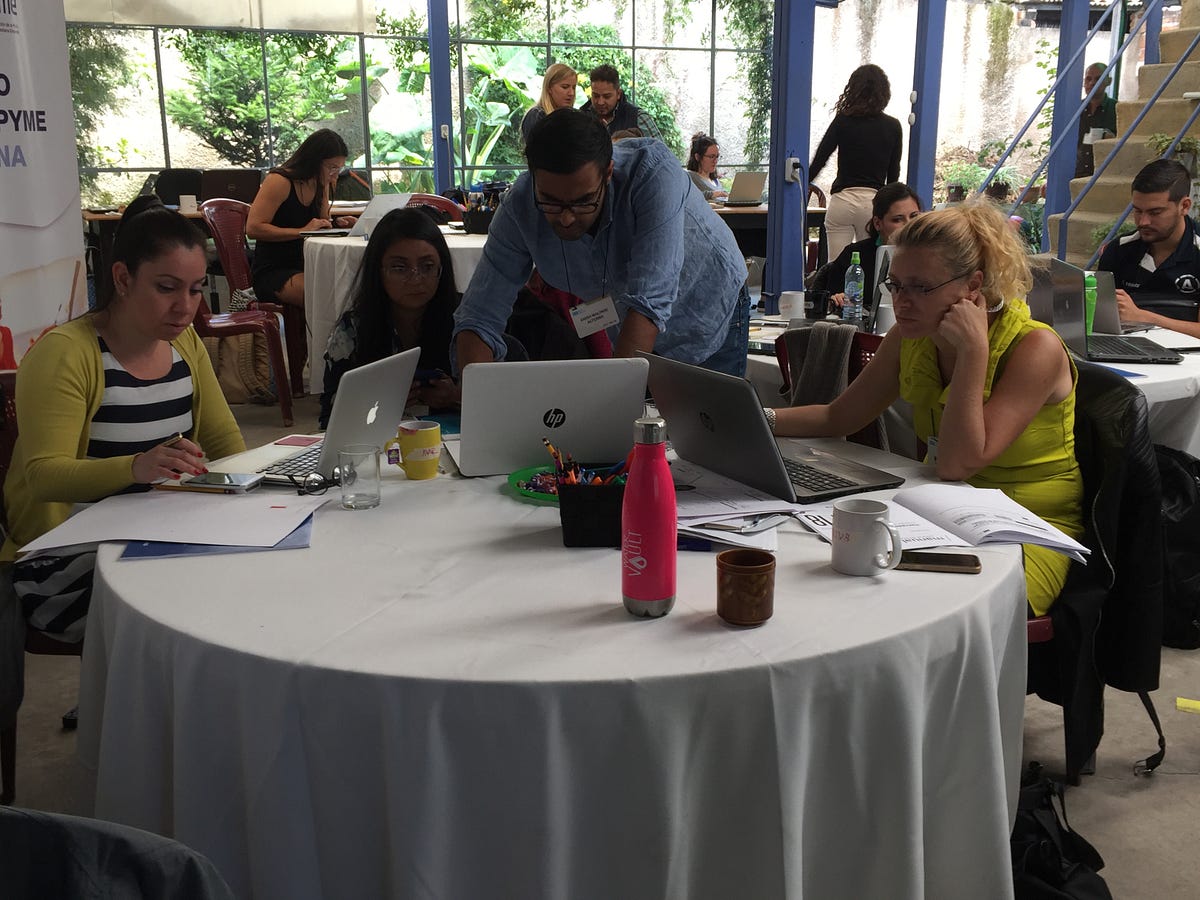

I will never forget the time we revamped our signature five-day workshop. We laboured long hours, researching, creating, fighting and ordering late-night pizzas. We were nervous before the start, but after, the feeling of success was priceless.

Many of us were unpaid fellows back then, but it didn’t matter. In fact, that made it that much sweeter— we did this because we cared for our entrepreneurs, and the pure elation of believing in something and making it happen is priceless. No chunky New York bonus has ever made me feel that way.

There was no way I was going to leave in six months. Uh oh, the OG plan just changed.

The next six months in Guatemala were even more fruitful. I got more responsibility and ownership, took on a bigger role with internal operations and led the negotiation, implementation and training of the organization’s internal IT infrastructure.

Many non-profits lack technical prowess — there aren’t enough STEM-skilled folks in the space which leaves gaping holes. We need more people filling these holes. I had some (not extensive) experience with these holes and I quickly realized that my ability to add value became my ticket to more exposure and learning. That would be a constant through this custom MBA of mine.

Also, I realized that there is no rush to get into the social impact space. What’s more important is to build hard skills and gain valuable technical experience from wherever you can, and then make the jump. There were a couple of other fellows there who I felt didn’t have enough experience nor a clear skill-set to add significant value with. This didn’t mean that they didn’t grow, it just meant that it was harder for them. Learning about the impact space isn’t as hard as learning a technical skill.

My last three months in Guatemala were tough. I was leading a full-scale tech implementation alone and was also handing off my key responsibilities to a new crop of hires. As important as that was, it wasn’t fun. Letting go of your baby is hard. I thought I’d have to have an actual baby to learn this.

I was flattered when Alterna offered me a Director position and to be a part of their future, but my evolved plan held strong. And the leadership team understood — I had always been consistent about starting something in India, and that consistency made it easier to communicate my next steps.

It turns out that having your big goal etched in stone makes decision-making easy and communicating your decisions even easier.

I remain connected to them today with somewhat of a ceremonial position on the Advisory Board, but Alterna and Guatemala will forever have a small piece of my heart.

Expense Breakdown in Guatemala:

- The first month of intensive Spanish classes and living with a host family cost me $836.

- The next 14 months rent was $200/month and living expenses (food, etc) were between $300 and $400 / month. Yes, Guatemala is cheap.

- For 8 of the 15 months I was there, I got paid ~$1,400 / month. I didn’t negotiate because I wasn’t looking to make money (I negotiated responsibility instead) so there could be some upside here.

- If I add-in around $2,000 for additional travel in and out of Guatemala that I wouldn’t really incur during an MBA, I would still end up breaking-even.

Stop 2: Nairobi, Kenya

After over a year in Guatemala, nine months longer than ‘planned’, I knew that my stint in East Africa had to be a little more constrained — no more than six months.

If the goal is to start something in India, I can’t just keep frolicking around the globe, delaying the inevitable. But working in sub-Saharan Africa seemed like an important step in this custom MBA of mine.

Shoddy as this sounds, the income per capita, the infant mortality rates, and disease-inflicted deaths in parts of Africa are among the gravest. Add that to the exploding youth population, the lack of jobs, and the rising temperatures, and what the continent is drifting towards is a largely young population of two billion by 2050, struggling to find employment as the world boils over. There could be a lot of other things that boil over as well.

But don’t get me wrong — there has been a ton of progress over the last few decades. Overall, as much as we shouldn’t generalize, African countries are freer and more developed than they have ever been. There has been innovation and expression, a better quality of life, and a Twitterverse exploding with opinion. It’s better, but there is still a long way to go.

And that’s why there is a lot of game-changing work being done there, especially in the social sector. So, I had to work there.

This time I was looking for more depth — i.e. working more closely with a couple of entrepreneurs, rather than at a more superficial level with many entrepreneurs, which was the case in Guatemala.

An email from the incredibly helpful Social Enterprise Jobs Google Group landed in my inbox that talked about a certain Amani Institute. It was new but what I liked about a program they offered was that it involved a four-month apprenticeship in Nairobi with local social enterprises / NGOs.

It also promised just enough coursework in some of the softer skills that I had been craving, but wasn’t necessarily ready to stretch for — leadership, management — some of the soft stuff that had haunted me towards the end of my stint in New York. Bingo.

I applied and soon thereafter, I was on my way to Nairobi as an Amani Fellow. I think I would have gone either way, but I was glad to go there with some structure.

The six months in Nairobi were intense. We worked for three days a week and had classes three days a week. The Sunday that was left hanging, left us fellows only wanting to hang around and do nothing.

I was apprenticing with a social enterprise that was trying to fight poverty through job creation in the urban slums of Kenya — where on my first day, we were marginally, indirectly tear-bombed.

More importantly, they are trying to do similar things to what I want to do in India. So, the learning curve was as steep and healthy as any wealthy education, if not more.

They did a lot of things well, but where they struggled was in finding operational prowess. Sadly, in the impact space, this is common.

While there is a ton of passion and drive in the social sector, there aren’t enough seasoned operators or technical folk. Add all that to the lower pay, and what you’re left with are inefficient organizations with tiny technical expertise and gigantic hearts. Burn out is more common than you’d imagine and it happens without any splurging compensation that at least some of the corporate burnouts can fall back on.

Through the Amani Institute, I also got to work with a social entrepreneur from Tanzania. His story is tragically inspiring, and it inspired me to work with him. He runs a non-profit focused on empowering Tanzanian youth and he was trying to figure out how to transition from a typical non-profit to a more financially viable social enterprise that was less dependent on donors. He had the field knowledge and I had the technical skills — and we complemented each other synchronously.

I learnt resilience from him, and I’m not saying that lightly. Despite having nothing, when he got a chance at life, he decided to give back. Despite being devastatingly knocked down multiple times, he hung in there. These few lines actually do injustice to the Everest he has had to climb, and is still climbing.

The six months in Nairobi whizzed by. But it felt like I had been there for an eternity, making new relationships and adapting to a new culture. It’s strange how time loses it structure as we sway from one perspective to the next.

I left Nairobi more ready than ever. I felt both validated and enlightened. I might have been extorted by bad cops with a gun in broad daylight, but I acquired a deep experience that geared me up for my next steps.

Expense Breakdown in Nairobi, Kenya:

- The Amani Institute Social Innovation Management program cost me ~$8,000. I applied before the deadline for a 50% discount / scholarship.

- My rent was $400 / month for a master bedroom and a private bathroom (with a massive bath tub) in a nice apartment with three other flatmates. No formal contract, just an informal email agreement.

- I ordered in a lot because of umm, “efficiency” and because UberEats is pretty efficient there as well. And taking into consideration that I was superfluous in my spending there, I spent about $600/month for food and other boarding-related activities. I could have been more umm, efficient.

- Overall, I spent about ~$17,000 for these six months for everything, without really trying to be cost conscious.

Stop 3: London, United Kingdom

You’re probably thinking: LONDON? Where did that come from?

Yes, the OG plan changed. A lot. But that’s the beauty of it, right?

One thing I realized in Nairobi is that I know enough about working in the impact space to start something on my own, but what I might be missing is some more technicality.

Remember the lack of operational prowess and technical expertise in the impact space I have been talking about? Well, I didn’t want to be that cliché or at least that was my rationalization. Yes, I could sing some decent finance tunes, but I wanted to learn more about data, and not just at a superficial level.

So, I found this immersive Data Science course that General Assembly offers in London (and other cities). It is a twelve-week bootcamp that tries to download everything it can about Machine Learning and Data Science at rapid speed. Magically, I had twelve weeks to spare in this custom MBA.

The course itself was intense to say the least. We had classes five days a week, 9am — 5pm and a ton of homework afterwards. But I thrived. I learnt how much I love messing around with data. I learnt that while I am not a naturally gifted musician, I do have a natural-ish knack for rows and columns full of numbers and symbols.

There are other institutes that offer similar programs across the world — some are fully virtual and / or after-work friendly. Meanwhile, Lambda School allows you to come into an income-sharing agreement with them. Which basically means you don’t have to pay anything upfront, only a percentage of your income after you get a job. And this past year, they had more applicants than Harvard.

Just to be clear, this type of course had nothing to do with the impact space. It didn’t need to be. This was about upskilling, and this new skill is applicable in almost every industry. My classmates ranged from engineers to statisticians to recent university grads. The age range was a couple of decades — from 20-year-olds to 45-year-olds. But none of them worked in the impact space.

The course was everything I wanted it to be and more. I feel like it opened a new box of possibilities that has been empowering. At the same time, in the spirit of keeping it real, if you want to be a full-time Data Scientist, just this course is not enough. There is more practice that you would need to do after, but the beauty of the course is that you gain enough of a base to leap off of.

I am not going to be a Data Scientist, but I want to use Data Science to make better decisions — to do better research, better monitoring and evaluation, and most importantly, to better allocate resources to solving this shitshow of a problem that is poverty. It also helps in solution-seeking — how can I use Artificial Intelligence to solve real-world problems?

And as a bonus, I got to spend three months living with my best friend. When else am I going to get a chance to do that at this age? See, a custom MBA also has its social perks.

Expense Breakdown in London, United Kingdom:

- The General Assembly Data Science Immersive course cost GBP 10k or ~US$ 13k.

- I didn’t pay anything for rent as I had the luxury to crash with my best friend. London is expensive so an average room should cost you around GBP 1,000 / month or ~US$ 1,300 / month.

- My best friend made me party a lot, so I did splurge on food and alcohol. So, including that and an additional $2,000 in travel costs, I spent about $18k — $19k for those three months.

- There are ways to do this cheaper — find a cheaper city, get a scholarship through the institute (I know they were offering a ~15% scholarship for women when I was attending the course), cook at home and party less.

Putting It All Together

So much for the original plan, right?

But that’s the beauty of the world we live in today. Some of us (and if you’re reading this, you are probably in the “us”) have the fortune to choose what we want to learn and how.

The typical MBA is not the only way out. In fact, it might turn out to be more expensive and less educational, which I strongly believe would have been the case if I pursued it.

Let’s summarize the expenses first, because well, that might be the most useful thing in this post.

Expense Summary Summarizing It All:

The table above is pretty self-explanatory.

If you analyzed it, you’re probably wondering why I didn’t pay rent in London. I was lucky enough to crash with my best friend, remember?

So, if you want to normalize for that and for the fact that I made money in Guatemala, let’s add rent for three months in London (GBP 1,000 / month) and remove the income I earned in Guatemala (just to be conservative). That brings total expenses to ~$51k which is still only 1/4th of what a Harvard MBA costs.

Reflection

The big lesson for me has been that once you figure out what you care about and are willing to dedicate yourself to that, then it has never been easier to pave your own path of learning. And learning never stops — cliched, but true.

I hadn’t even thought of this as “oh, let me do custom MBA.” I just went down the road I thought I needed to; so I could gain the skills that I needed; so I could working on solving the problem I wanted to solve.

I have also realized that true learning cannot happen only in the classroom. It needs an element of reality to complement all the theory. So yes, it all comes down to finding the right balance. Like most things in life.

It has been six months since I moved back to India. I have never been more focused and content. And I have never felt more ready to start a social enterprise focused on multidimensional poverty.

The Other Side

Look, it has not all been rosy.

I don’t have a fancy $200k Harvard stamp on my resume. Someone who does, commands immediate credibility — at least at a superficial, perceived level. If that stamp is important to you, then a top MBA is unbeatable.

There have also been times on the road when I felt very alone. I missed home, I missed having a home. I missed my best friends. I hated those cold showers. The internet was shoddy in most places besides London. The food in Guatemala wasn’t great. I was extorted by cops in Kenya which wasn’t fun. I had to stay away from committing to a relationship because I was always moving on. It seemed like I was always saying goodbye, while not knowing when I’ll meet those folks again. There was uncertainty and discomfort.

But it was all worth it.

And when all that feels worth it, you know you have grown.

Okay, enough. I have laid it all out. I’ll let you be the judge.

P.S. Parts of this post have been taken from other posts I have written in the past.

Spoken Word & Me

Spoken Word & Me

I happened upon spoken word poetry through my sister. She sent me this TED talk that Sarah Kay gave ages ago and I was sold.

When I saw her perform, I was consumed by the connection that she so simply established. There was vulnerability and authenticity, sprinkled with humility that drew me in to embrace the oneness that humanity beckons. It was a ray of light amidst the chaos that seemed to be engulfing my mind back then. I don’t think I have ever wept so hard.

Shane Koyczan was the other poet that shook my earth. If Sarah Kay is the reason I got into poetry, Shane Koyczan is the reason I started writing. Not dealt a favorable hand, Koyczan turned his depression into some of the most beautiful, heart-wrenching works of art.

I learnt that spoken word is this powerful, accessible tool that can unleash and unite, cradle and conquer, amuse and amaze. And that it is meant to be heard, not necessarily read. It is meant to be said aloud by the person who wrote it, emoting the visceral nature of hurt or joy that shaped them. I wanted to get in on this, stat.

But then, there was the other side to this whole spoken word thing that kept pulling me back.

Spoken word begs for vulnerability in a world that is focused on being unfazed, unmoved – “strong”. Apparently, being emotional is for wusses. So, for many, this art form screams eye-roll-worthy cheesiness – “embarrassing”, “awkward”. My best friends really try to like the spoken word I do, but it just seems too hard for them, too squirmy. A+ for effort, but it’s okay that it’s not everyone’s cup of tea.

I think the fear of ridicule made it harder for me to embrace this art form though.

I was living in New York back then. I quietly started going to an open mic at the Bowery Poetry Club every Sunday; just observing. The idea of getting on stage seemed like a wormhole that I wasn’t even looking to find. But whenever I got the chance, I went to see and hear. I saw and heard the likes of Sarah Kay and Andrea Gibson and Olivia Gatwood. I heard my almost-namesake Anis Mojwani shake the dust. I heard Neil Hilborn find beauty in the pain that OCD infuses. Consumption was enough, right?

Not quite.

It took me a year to gather the courage to get on stage. It was at the Bowery Poetry Club; it had to be. It was a place where encouragement was easy to find, where making a mistake was applauded, where courage was rewarded. It made me realize that there are times when being allowed to make mistakes is the most important thing.

Queue all the clichés – my legs were shaking, my voice was nervy, my hands were trembling. Overwhelmed with inexplicable fear, I ripped through my first ever piece, fumbling along the way, realizing that the perfect start is always an imperfect one.

And then, the tap opened. Open mics suddenly saw me contribute in addition to consume. In fact, if I didn’t get on the performer’s list, I’d be all mad. I would go an hour early at times to ensure that I got the perfect spot – not the first spot, the third or the fifth, depending on how confident I was in the poem I was going to perform; the more vulnerable the piece, the further down the list I wanted to be.

There is something about sharing explicitly, especially in a place where it is expected. I didn’t like going to just any open-mics. They had to be specifically for spoken word. And with that, New York was generous.

I feel like while society has accepted the art of musical performance as universal, it is still confused about spoken word. Maybe because it seems so easy – just get on there and say emotional shit, right? Perhaps. But it is its accessibility that makes it so powerful.

The fact that it is ridiculed is what made it important for me. Before this, I seemed hooked onto conformity. Because conformity seemed like the easiest path to be liked by everyone: don’t ruffle anyone’s feathers, don’t give anyone fuel to laugh at you, always “be cool”. Spoken word made me break through that trap to embrace what I thought was cool and connect with those that were open enough to embrace that.

So, I embraced and engaged – I performed as much as I could. At the Bowery, if you performed something new, you were always met with a “new shit” chant, and that became enough encouragement to always write something new.

So, I wrote, and I shared. I made new types of friends who hooted, snapped, laughed. I even got to the chance to perform for Sarah Kay at the Bowery, and my old friends just couldn’t understand what the big deal was. I got to attend a workshop by Shane Koyczan and see him live in India of all places in the world. And now, this has just become a thing I do.

And in that doing, there is a bunch of poems I wrote. And then I recorded them. And then I convinced my musician best friends (who try really hard to like my poetry) to write music for it. They took awfully long, but they did, and they did so quite wondrously. And now I’m putting it out there because Liz Gilbert said so. And because Brene Brown says that it’s important to be vulnerable. But mostly because I want to.

The first piece (first video up top) is something I wrote when I was in Guatemala. I was on a newfound path but missed the best parts of my old path. Because everything about a bad thing isn’t bad and everything about a good thing isn’t good. You might find your own meaning in all that jazz though.

And there’s a whole album out that you can listen to on all the streaming services out there.

Here’s an album worth of poems:

P.S. My 10-year old niece, Janakee, along with her mother, Aditi Bhabhi, helped design my album art.

Where Do I Start?

I have been on a nervy adventure of starting a social enterprise focused on multidimensional poverty here in India. For those that have been following, some of y’all are probably wondering — dude, get with it already. Noted, noted, almost there.

For now, here’s where my heads at.

When it comes to starting a social enterprise, it’s super important to understand your burning, or the depth of the problem you care about. It’s a never-ending process, but probably the most important.

Over the past three years, I have been fortunate to have the resources to really understand the poverty space. I took all that and some of the skills I have nurtured to break down the problem in the detail that I needed. If you’re curious, here it is in all its pomp. If not, then this is what’s relevant:

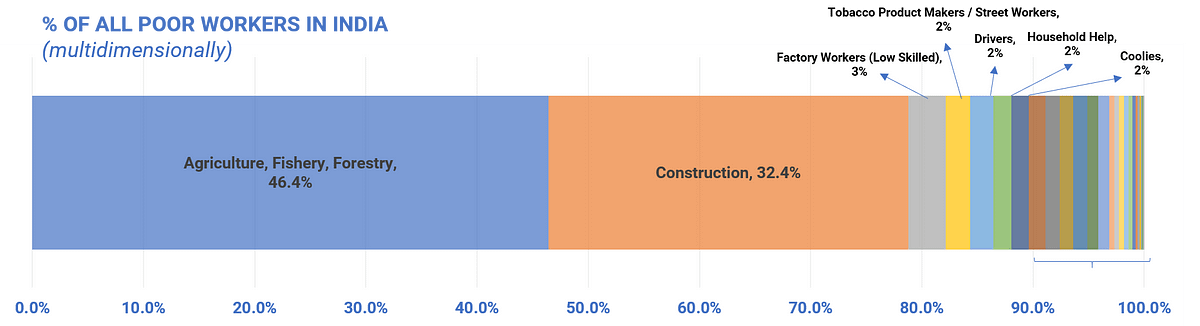

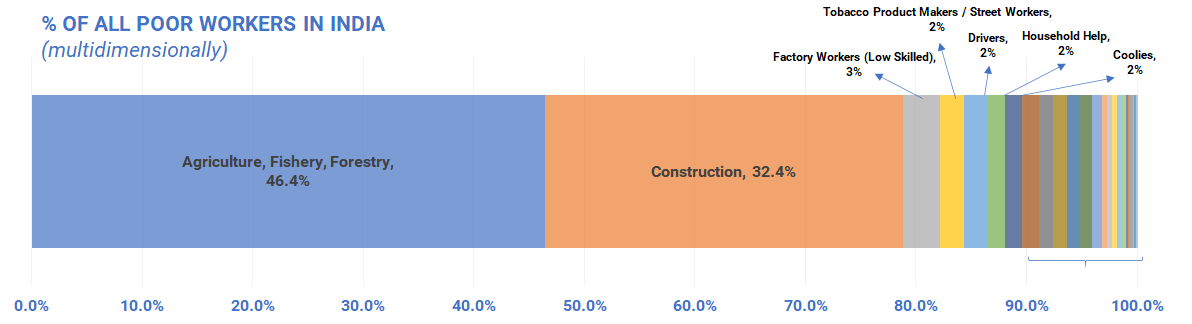

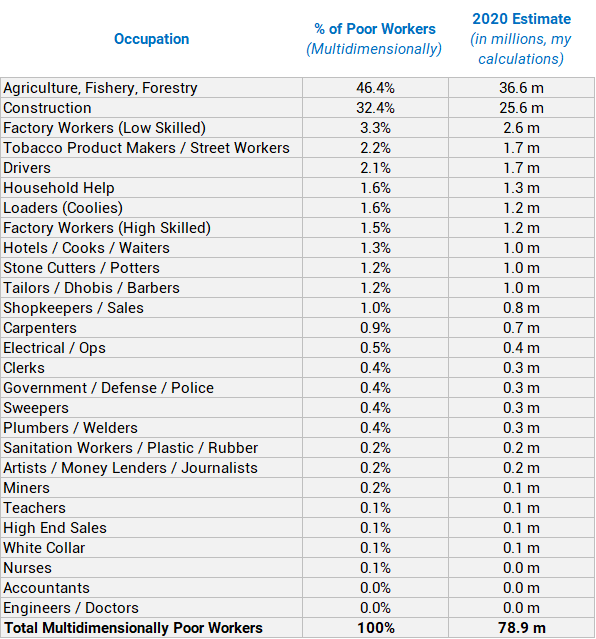

~300 million people in India (or ~22%) are multidimensionally poor, and below is how they break out by occupation.

Based on the 2012 India Human Development Survey (IHDS) and my calculations.~79% of all poor workers in India (~62 million) work either in agriculture or construction. Low skilled factory workers come third at 3%, which is substantially lower. The rest are 2% or less.

So if I was to follow my own research, it’s pretty clear. Focus on farmers. And if I want an urban life, focus on construction workers. Those are the biggest pieces of the poverty pie and they need the most amount of attention.

But that’s not what has been on my mind.

I have been drawn to the waste management space (specifically solid waste) in India for a couple of reasons.

One because it employs some of the poorest — waste pickers, scavengers, rag pickers. And two, because there is value in waste that can fuel financial sustainability, and make mother earth better.

With regards to the first reason, there isn’t a whole lot of data available that isolates the poorest in the waste management space. Case in point: the data set I used in that graph-y analysis mentioned earlier. Out of the 50,000+ entries that were collected, I found maybe ten or twelve entries that had their job description as “waste picker” or a Hindi-equivalent. Some were grouped under agriculture, some under construction, some under coolies, some under sweepers, but to cut a long story short, this is not a category that’s looked at closely from a macro research perspective.

There is probably some overlap with the “sweepers” category and there might be some noise is the “sanitation workers” category, but it is not explicit. And that matters because being a municipal sanitation worker versus a rag picker is significantly different.

Here’s an exert from Assa Doran and Robin Jeffrey’s excellent book, Waste Of A Nation that throws light on this darkness (emphasis my own):

On the frontline of rubbish recovery are the people who collect waste. Scavengers, waste-pickers, ragpickers — by whatever name they are called, they carry a burden of poverty and prejudice. They are commonly regarded as dirty people, dislocated migrants, indifferent to basic hygiene. Their scavenging of open dumps is taken as an affront to social order and urban sanitation. And the fact that they work in places that were once regarded as no one’s land, or the commons, but now are often claimed by the state or private owners makes them ready targets for police harassment. Little is mentioned about the effects of their work in reducing the amount of rubbish destined for landfills.

The most vulnerable scavengers work in grim conditions on mountainous landfills, such as Deonar in Mumbai, Okhla in Delhi, Dhapa in Kolkata, Kodungaiyur in Chennai, and less prominent dumps like Belgachia at Howrah in West Bengal. Estimates put scavengers’ life expectancy at thirty-nine years. In their search for defecation space and salvageable materials, adults and children have learned to tread lightly. At Deonar “there are cracks and crevasses” that can trip, and even swallow, waste-pickers, Doron was told when he visited the smoldering mountain, “and kids inhale the toxic fumes” spewed by the mountain. In 2017, a landslide at another site, East Delhi’s giant Ghazipur dump, killed two people.

The usual competition on open dumpsites comes from rats, dogs, pigs, monkeys, and birds — all thriving on mixed rubbish. For ragpickers, sporadic fires generate an acrid haze that makes breathing difficult and presents the greatest health risk. Waste workers register high levels of tuberculosis.

Doron, Assa. Waste of a Nation (pp. 211–212). Harvard University Press. Kindle Edition.

Also, Kaveri Gill wrote an entire book on poverty and waste-pickers based on her research in Delhi. It’s a little dated (2007–10), but she does have estimates for amounts they earn. When adjusted for inflation, waste-pickers make about 30% less than urban construction workers and low-skilled factory workers.

High-level estimates peg the the number of waste pickers in urban India between 3 and 5 million. Another exert from Doran and Jeffrey on how elusive a real number really is:

“The census does not have an occupational category for ragpickers or waste-pickers. In New Delhi, a common estimate was that between 200,000 and 350,000 people worked as waste-pickers in an urban area of 16 million people in 2011. Rough calculations suggest that India’s 53 cities with populations of more than 1 million support close to 2 million waste-pickers, and its 465 cities with populations between 100,000 and a million sustain a further 1.5 million. At that rate, urban India in 2011 had at least 3.5 million people handling waste every day, and these calculations do not include the manual scavengers who clean the dry latrines described in Chapter 3.”

Doron, Assa. Waste of a Nation (p. 189). Harvard University Press. Kindle Edition.

For the record, there are also about 2.5 million “manual scavengers” who jump into sewers and cesspits, and I am not even looking to focus on them for now.

How do you quantify this sort of poverty? Of a group that barely gets isolated from a research perspective. Of a group whose life expectancy seems so absurdly low that it’s hard to believe. Of a group that competes with rats, dogs, pigs, monkeys and birds. Of a group comprising low caste folks and stigmatized minorities that either way get treated like shit. What statistical weight do I put on what factors to spit out an index that quantifies inhumanity?

Look, this does not mean that being a poor farmer or a poor construction worker or a poor tobacco product maker isn’t as bad. Those lives need uplifting as well, and in some dimensions, even more than waste-pickers. For instance, urban tobacco product makers earn almost half of what urban waste-pickers earn. And when it comes to poor farmers and poor construction workers, we have already seen that in absolutes, they encompass countries worth of people.

But where do waste-pickers lie in a world where even holistic data evades them? Even if there was data available, it’s not just as simple as what the “data says”.

There are other philosophical factors at play here that are almost impossible to program in while contemplating starting a social enterprise. Such as the importance of a viable starting point, the future of work, the probability of success (where the metric is the # of people lifted out of multidimensional poverty) and the scalability potential of a model with high, untapped intrinsic value. Each of these factors could probably do with an entire book worth of explanations, but I’ll spare you the additional dramatic justifications, at least for now.

Or maybe I am overthinking it? Rationalizing my gut in true Haidt-ian fashion? Maybe it is as simple as what the data says and I just focus on farmers and construction workers and tobacco product makers?

This back and forth isn’t startlingly novel, so it’s not like Jesus has returned and I need to reevaluate everything. It has been hovering around for a while. The only difference now is that it is time to make a decision.

P.S. It’s a strange time to share — the pandemic, the isolation, the emotion-filled search for purpose. It’s almost like you’re not allowed to talk about anything else. I felt a little weird putting this out there, more than the usual. And yea, just that.

Who Are The Poor Of India?

Ever since I quit the corporate world, the story I have been telling myself is that I want to work on uplifting the poorest.

I am data-man, or so I would like to think. So, it is essential for me to understand the size and depth of this problem of poverty. And how do you even define poverty? Let alone quantify it?

Over the past three years, I believe I have earned a decent understanding of it. This is an attempt at formalizing that understanding.

First, what is poverty?

Believe it or not, this isn’t straightforward. There are four different ways to look at it:

- Absolute Poverty: This draws an income line across the world and everyone under it is poor and everyone above it is not poor. There are different lines, the most popular being the “extreme poverty” line which is $1.90 / day adjusted for purchasing power parity. Which basically means let’s keep things apples to apples, not apples to moons. Pros and cons here and you can think about that all day.

- Relative Poverty: This arranges people within a certain population according to income, and those that fall in the bottom tranche are considered poor. A good way of understanding this is that while there is no absolute extreme poverty in the U.S., there’s a ton of relative poverty. Relative poverty will almost always exist. Absolute poverty doesn’t need to.

- Multidimensional Poverty: This is my preferred definition. It is based on the tenet that poverty is more than just a lack of money — it is a lack of access to healthcare, education and a decent standard of living. It just falls short of including dignity, but dignity is something even the Gods won’t be able to quantify. Intuitively, this increases the total number of poor because it increases that basic standard we aspire to for humanity.

- Hunger: If you’re absolutely poor, you’re probably hungry. So, sometimes, looking at the hunger index is also a good way of gauging pain. Sounds morbid, but it is easier to quantify.

And these definitions are just skimming the surface of the ocean that is measuring injustice. There are also recall methods, survey nuances, time-sensitivity issues, and other permutations that give data-abusers enough ammo to craft any story that fits their narrative.

I’m going to avoid doing that.

Okay enough jargon, so how many people in India are poor then?

You guessed right; there are many different estimates for this as well. But I promise I’ll end this section with somewhat of a reasonable number for us to anchor to.

Meanwhile, here is a bunch of poverty estimates for India that you’ll see flying around in the public:

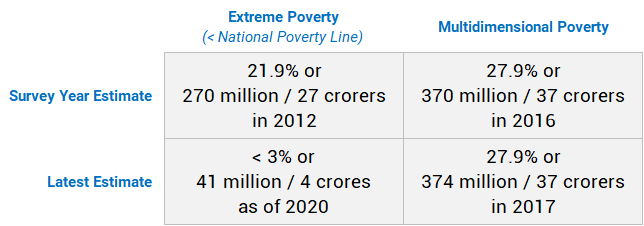

Image by Author, Sources: 2012 Extreme Poverty, 2020 Extreme Poverty, Multidimensional Poverty

It’s important to consider what the numbers were during the survey year because that’s when data is (or should be) the cleanest. Estimates based off that add more assumptions to an assumption-laden world, which only contaminates the truth.

For instance, I don’t fully believe World Poverty Clock’s assumption that India has only 40 million extremely poor people right now. Either way, I don’t think looking at extreme poverty is the best way of looking at specific country’s poverty — it’s singular, and poverty is not singular. So, let’s drop that and progress.

Multidimensional poverty on the other hand, is hands-down the best way to look at poverty based on what’s out there. It was developed by Oxford University in 2010 so there’s some credibility for you. This metric is hard to calculate but not impossible. Enter UNDP. They have been nice enough to calculate and aggregate this for us.

Ahh, I’m finally getting to the point.

In India, in 2017, 28% or 374 million were multidimensionally poor. I did my own math from an incredible human development dataset from 2012 using a similar thought process, and my estimate was ~34% for back then. So, taking all that into consideration, and the fact that India has been growing economically (at least pre-COVID), I think it is fair to assume that today, India has a multidimensional poverty rate of 20%-25%. Extrapolating that to current population estimates (2020), that’s somewhere between 274 million and 342 million people.

To make it a little easier, let’s settle for a number somewhere in the middle which conveniently comes to 300 million people that makes up ~22% of India’s population.

There, as I promised, a reasonable number we can anchor ourselves to.

Fine, so who are the poor?

It’s now time to get to the meat of things. If you’re familiar with the social impact space, none of the above should have been bombastically revealing. The following though? Maybe.

The question that was grappling my mind (and my heart) is who exactly are the poor? And not just from a meta, philosophical perspective, but from an actionable, data-driven perspective.

Farmers, construction workers, waste-pickers, Dalits — that’s what comes to mind right off the bat, but how many of them? By how much? Who else? From what perspective are they poor — health, education, income? And what about security guards and dhobis and coolies? Are they poor? Not all of them, obviously, but how many?

So yes, if work is the center of sustenance of life, I was curious what type of workers fell under the landscape of the poor in India.

I happened upon an incredible human development survey from 2012 that had data at an individual and a household level for over 40,000 households and over 200,000 individuals. It was representative and has been used by many impact strongholds including the International Labour Organization as recently as 2018. Credibility.

I isolated the 50,000 individuals who were mostly working, cleaned up some of the occupation data, mapped it, calculated a reasonable version of multidimensional poverty based on the data that was available, and voila! Here is how I answered those grappling questions of the head (and the heart).

Image by Author, Based on 2012 India Human Development Survey (IHDS)No surprises here. ~79% of all poor workers in India (62 million) work either in agriculture or construction. Low skilled factory workers come third at 3%, which is substantially lower. The rest are 2% or less. The small revelation for me was the tobacco product makers (beedi-makers) at 2.2% or almost 2 million. They earn the lowest on average and almost a third of all of them are multidimensionally poor. Interesting cognitive dissonance here: tobacco is bad for you but what happens to the millions of people who make a (poor) living out of making tobacco products?

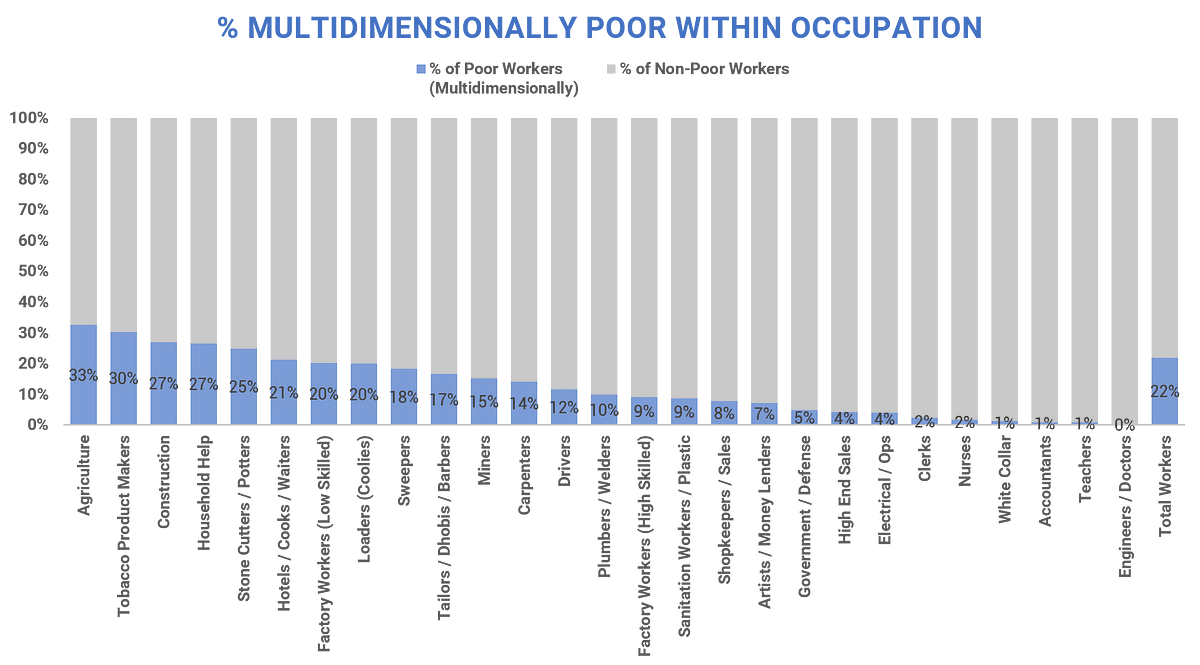

Image by Author, Based on 2012 India Human Development Survey (IHDS)We now know that most of the poor are farmers and construction workers. But they also constitute the largest proportion of all workers in general. So what percentage of farmers, and construction workers and drivers are poor?

Image by Author, Based on 2012 India Human Development Survey (IHDS) and my calculationsAlmost a third of all agricultural workers are poor. Construction workers are also above the average, and so are tobacco product makers, household help and stone cutters. And remember, these folks are not just poor from an economic perspective, they are also less educated and much more at risk with their health.

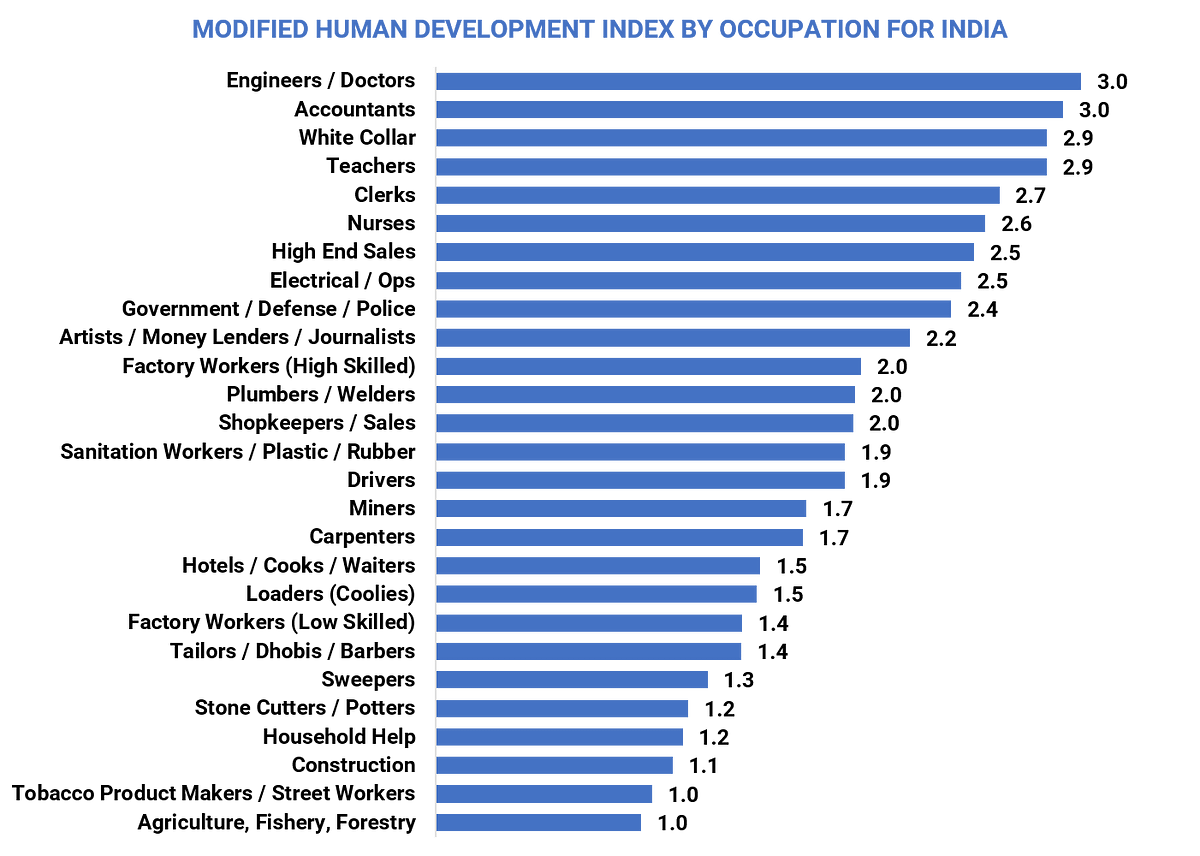

Modified HDI

Inspired by UNDP’s Human Development Index (HDI), I created a morphed / modified version of it for the various types of workers of India. Why morphed? Well because I was limited by the information available by worker in the data set I was using. Enough excuses, enough disclaimers, it is still helpful, albeit not telling us anything spectacularly new.

Similar story — farmers, tobacco makers, construction workers, maids and stone cutters live a disdainful life.

One of the morphs I sizzled into this modified HDI was the inclusion of a social status index. This is a tad bit controversial and it’s pretty sad that I even have to include something like this, but in India, it’s just not advantageous being born into a lower caste or a marginalized minority. Adding that dimension into the mix pulls the occupation group of sweepers lower down. Most sweepers and sanitation workers (~60%) are dalits (low caste folks). Most stone cutters are also dalits and many are adivasis (protected tribes). This shouldn’t make a difference, but it does, and not for the right reasons.

Anything else?

Look, this is still far from perfect. Just because many farmers and constructions workers are poor, doesn’t mean that they are the poorest. Just because some people have money and healthcare and education, doesn’t mean they live happy and wholesome lives. Quantifying dignity, happiness, pain and injustice are hard if not impossible.

But that doesn’t mean we can’t try. And that is not an excuse to not do anything about it.

So now what?

Let’s get at it. As effectively and quickly as we can, while still ensuring we seek systemic solutions that solve this problem for the long run. I don’t think we need a quick fix per se, I think we need long-term fix sooner rather than later. We have made enough progress today to envision a world where multidimensional poverty does not exist.

I essentially did this analysis for myself. I will start a social enterprise focusing on this very issue, and wanted to understand it better. And despite breaking the problem down, I am still battling through other dimensions that are hard to reconcile.

If you have any epiphanies, please decorate me with them.

A note on the sources for this post:

The base for the majority of this analysis is the micro-data of the India Human Development Survey: Desai, Sonalde, Reeve Vanneman and National Council of Applied Economic Research, New Delhi. India Human Development Survey-II (IHDS-II), 2011–12. ICPSR36151-v2. Ann Arbor, MI: Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research [distributor], 2015–07–31. http://doi.org/10.3886/ICPSR36151.v2

I created and cleaned some of the data to make it more sensible.

I have cited sources for all one-off data where I have used them.

Any questions / concerns, please do not hesitate to reach out. Am a believer in full transparency.