A Bridge For Change In Tanzania

Ocheck Msuva’s story needs to be heard.

Rejection

Ocheck’s existence began with rejection. When his mother found out that she was pregnant, his father refused to accept her pregnancy. He was born much to the chagrin of his family, who lived a poor life in rural Tanzania. So much so that Ocheck was sent to live with his aunt. His aunt gave him shelter but never took him as one of her own. When you don’t have much in this world, even blood isn’t enough to warrant love.

The first time Ocheck tried to kill himself was when he was twelve. Early education is technically free in Tanzania if you can pay for your own uniform, supplies and examination fees. His aunt refused to buy him a uniform for school, espousing the burden of taking care of Ocheck in addition to her own children. And this was the final straw. If nobody wanted him, why exist? He found a tree, and some rope. While trying to setup this killing contraption, some people happened upon the tree. Scared, he ran.

The second time Ocheck tried to kill himself was when he was fourteen. He had stolen a uniform from a neighbour so he could somehow make it to school. But after dragging on for a couple more years, life still did not seem worth it. This time he found some pills. But fortunately, or unfortunately, they weren’t enough. Fate can be cruel to even the most innocent. Belonging is how humanity has survived and thrived through the ages, and to deprive a child of it at his most malleable and vulnerable time is to give him no reason to live.

Hitting The Streets

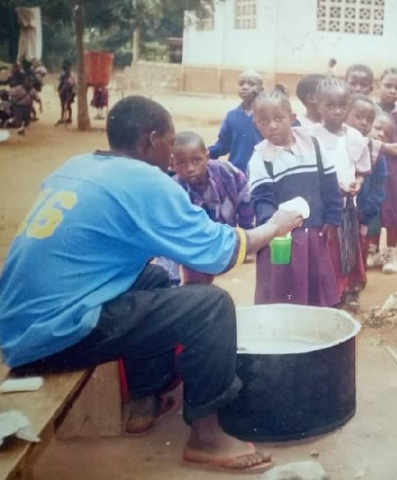

At fifteen, Ocheck felt that enough is enough. It was time to try this “life” thing on his own. He dropped out of school and ran away from his aunt’s place to live on the streets of Iringa. The streets bought him a little more luck. He found small jobs to survive. He cooked meals for kindergartners and at one point, even opened his own little street stall that sold fries outside of a church. He saw wealth, not his own, but of his rich employer who he worked for as a house boy. He once told the wealthy man who employed him that he dreamed of going to university and becoming someone. To this, he replied, “If a foolish person says stupid things, I normally do not listen.”

This crushed Ocheck. But his takeaway was that even the wealthy can be miserable. And early on, despite not having anything, he learnt that maybe money doesn’t bring you happiness. Through all of this, Ocheck still held on to a dream. And as cliched as this sounds to us, that dream of being someone, standing for something and belonging, is what kept him going

.

A Dream

Done with the street hustle and with a little money in his pockets, Ocheck went back to school. He started focusing on his classes and his scores rose. He spent his Sundays as a pastor, preaching and singing in the local church. His excellent grades got him admission into the University of Dar Es Salaam, and he took on a loan to fund his bachelor’s in political science there. Slowly but surely, Ocheck finally found his rhythm and his dream of becoming someone started turning into reality.

During and after University, Ocheck scored some well-paid gigs courtesy of the seeds he had sowed earlier. This gave him a bit of money and the gears in his head started turning. He realized that there were thousands of kids like him who had been discarded from their families and had nothing. He realized that there were thousands more whose dreams had withered away because reality was just too real. Ocheck believed that the only reason he survived was because he had a dream. And against all odds, he made his dream of graduating from University and of becoming someone a reality. He believed that if he could give the youth of Tanzania the power to dream again, and the encouragement to give their dreams a chance, he could instigate real change in Tanzania. So, in 2015, with the bit of money he had saved up, instead of looking for a comfortable, well-paid job, he decided to start Bridge For Change.

Being The Change

Bridge For Change (BFC) was created to empower the youth of Tanzania through training sessions, career support and mentoring. It blossomed quickly. Within three years, it had impacted over 18,500 students across 38 schools, and had mentored over 600 students at a deeper level while working with the likes of UNICEF, Vodacom, The Goodall Foundation and Cambridge University. BFC held “dreamscaping” sessions where school students were encouraged to draw out their dreams and then to find a path that took them there. And in the middle of all this, stood the inspiration of Ocheck — a testament to the fact that despite the gravest of odds, it only takes a dream to garner hope and strive towards the seemingly impossible.

In mid-2018, Ocheck started to feel that something wasn’t quite right at BFC. They were growing and making impact but were wildly dependent on their donors. What they were doing was not scalable. It felt like all that was important was ensuring that their donors were happy and that they were hitting the ambitious impact numbers demanded by them. There seemed to be ample width but not enough depth. All this made Ocheck hit the pause button and re-evaluate what the right next step for BFC was. And that brought him to Nairobi.

When I Met Ocheck

I met Ocheck in Nairobi as a part of the Amani Institute program. He was a fellow there trying to figure out where BFC needed to go and I was a fellow there hungry to learn by working in the social enterprise space. We couldn’t have come from more different backgrounds. While Ocheck’s aunt was looking for ways to get rid of him, any of my aunts would have adopted me in a heartbeat. I was blessed with an incredible family that pushed me beyond my limits. I didn’t need a dream to survive, instead I thrived on the fear of not making my dreams a reality — I had it all, how could I not?

Ocheck’s story is compelling but what sealed it for me was his ability to face the brutal facts. He told me that there are some significant systemic issues in the education system in Tanzania which severely impact the productivity of their youth. He said that they need to stop pretending that the solutions can only be found in Tanzania. “What’s important is that we find the best solutions for our youth, irrespective of whether it is from inside or outside of our country.”

This honesty struck a chord. Half the world talks about the “white saviour” issue engulfing most of Africa, and here you have a Tanzanian, who has been to hell and back, who is willing to put his pride aside and is committed to finding the best solution for the problem he has himself struggled with, irrespective of whether it comes from a Tanzanian or a “white saviour.”

Ocheck had enrolled in the Amani program looking to transition BFC from a typical non-profit to a more financially sustainable social enterprise. That’s where I saw an opportunity to add value. The Amani program allows fellows to pair up and work on projects together. This project was real. Ocheck was real. So, I started making my case, and he bought in.

In the next four months, we stripped down the organization and started to build it back up. We re-evaluated the extent of the youth productivity problem we were trying to solve in Tanzania and the numbers were glaring. We juggled ideas ranging from trying to create jobs by catalysing wheat farming in rural Tanzania to formalizing the informal real estate labour force. We finally settled on something less ambitious but more realistic. We didn’t want to part with the ambitious ideas though so we put those aside under the label “eventually.”

It was not all hunky-dory. Ocheck and I have different skill-sets with different working styles from different cultures. I am almost infested by the hustle and bustle of maximizing productivity from my Corporate America days — low in patience, high in productivity. Ocheck embodies a different kind of hustle, one filled with patience and persistence. I brought in the Excel skills, the PowerPoint skills and the strategic structure that has been chiseled in my DNA, while he brought in the local context, the history, the commitment and the direction. I didn’t pretend to know anything about Tanzania and the Tanzanian youth and Ocheck didn’t pretend to know anything about Finance. We played to our strengths while respecting what each brought to the table.

It was still frustrating in parts. My expectations skyrocket for those I admire, sometimes beyond reason. At times, I was hard on Ocheck, really hard. But he took it like a champion. I have never seen anyone take feedback as well as he does. There was a genuine desire to grow and he bloomed — and that’s in line with the research that’s out there — surround yourself with people who can give you objective hard feedback; our minds are too adept at rationalizing even the most obvious shortcomings.

Reflection

All this made me reflect deeply. There I was, coming from an extremely privileged background, with the audacity to berate for unreasonable expectations. What right did I have to do that? Yes, the past doesn’t matter when you’re in the present, but you can’t discount it either. I have spent my entire life educating myself in the most privileged schools, never worrying about a meal. Ocheck’s history is different, and that matters. The grit he has exuded to make something out of nothing is something I can never fully comprehend. His courage to invest the little good fortune he got into becoming an entrepreneur is something I will never be tested with. He has his skin deep in the game that he has dedicated his life to winning. He serves as an inspiration for me like none other. To never give up. And for that, I could not be more grateful.

After the Amani course, Ocheck invited me to Tanzania to run a couple of sessions for BFC. I had the privilege of teaching human-centred design to about fifty university students and running a mini-training session for his team on learning how to learn. I probably learnt more from them than they did from me. But more importantly, I got a glimpse into Ocheck’s world. I got to see in-person what Ocheck had been talking about — there is a gap in the Tanzanian education system that needs to be bridged. I also got to see the admiration Ocheck has won from the people around him. He might not have a family, but one Saturday morning, some of the brightest minds of Tanzania — PhDs, engineers, UN fund managers — showed up on their own stead to brainstorm ways to improve the productivity of Tanzanian youth. And they showed up for Ocheck. Not only because of who Ocheck is and what he has done, but because of what he stands for. As much as this is Ocheck’s story, what makes me believe in him is that this is not about him, this is about something bigger.

And that’s what I have bought into — what he stands for. When we accepted our differences, there was something magical that developed in the way we worked together. There are powerful synergies if you can learn how to combine local commitment with foreign expertise. So while the “white saviour” complex is a thing, there are ways to work with committed local leaders as long as you’re willing to not pretend you know everything and drop the ego.

There is still a long way to go for BFC. It has not been easy, and it is not going to be easy. But after what Ocheck has pulled through, this might be more of a cakewalk.

Humility

I remember one morning in Nairobi, when Ocheck and I were walking to class, he said, “Anish, I really want to forgive my father, but I don’t know how.” This is the same father who refused to acknowledge Ocheck as his son for the first twenty years of his life, who threw him out of the house to fend for himself. I didn’t know what to say.

In Tanzania, Ocheck was adamant that I visit his house — a little studio which my one month of rent in New York could cover almost six years’ worth of rent for. He said, “Anish, in Tanzania, as a guest, I must host you at least once. And yes, this place is small, but my landlords treat me like a part of their family.” He pulled out a photo album and walked me through his past. There was a photo of him as a cook serving little kids while he was on the street. There was one from when he had built his own little street stall that sold fries. There was another of him as a house boy. Another as a pastor, one of him singing, one of him during his graduation, and a few more that he had somehow managed to hold on to. There were no pictures of him before the age of fourteen. And to think, my little one-year old niece already has thousands, enough to fill a truckload of photo albums.

Despite everything, there is immense joy in Ocheck. There has been nothing simple about his life, yet he lives simply. He is not perfect but he champions humility, grit and faith, and an unwavering belief that his vision of a more productive, developed Tanzania is not just a pipe dream. This humility has humbled me. And for all that and more, this is an unfinished story that needs to be heard.