Football, Scaling Depth & Stress

“We use football to heal minds in urban slums,” said Victor, as we squeezed into the back of a bus in Nairobi.

I was back in Kenya after half a decade for a fellowship summit.

Hard work pays off, and sometimes good people recognise it. And some good, hard-working people are brave enough to bring other good, hard-working people together to be better.

That’s The Global Good Fund.

It brought fifteen social entrepreneurs from all over the world together in Nairobi for a week – to reflect and reassess, to reconcile the rancour that even good things sometimes reveal.

And that’s where I met Victor.

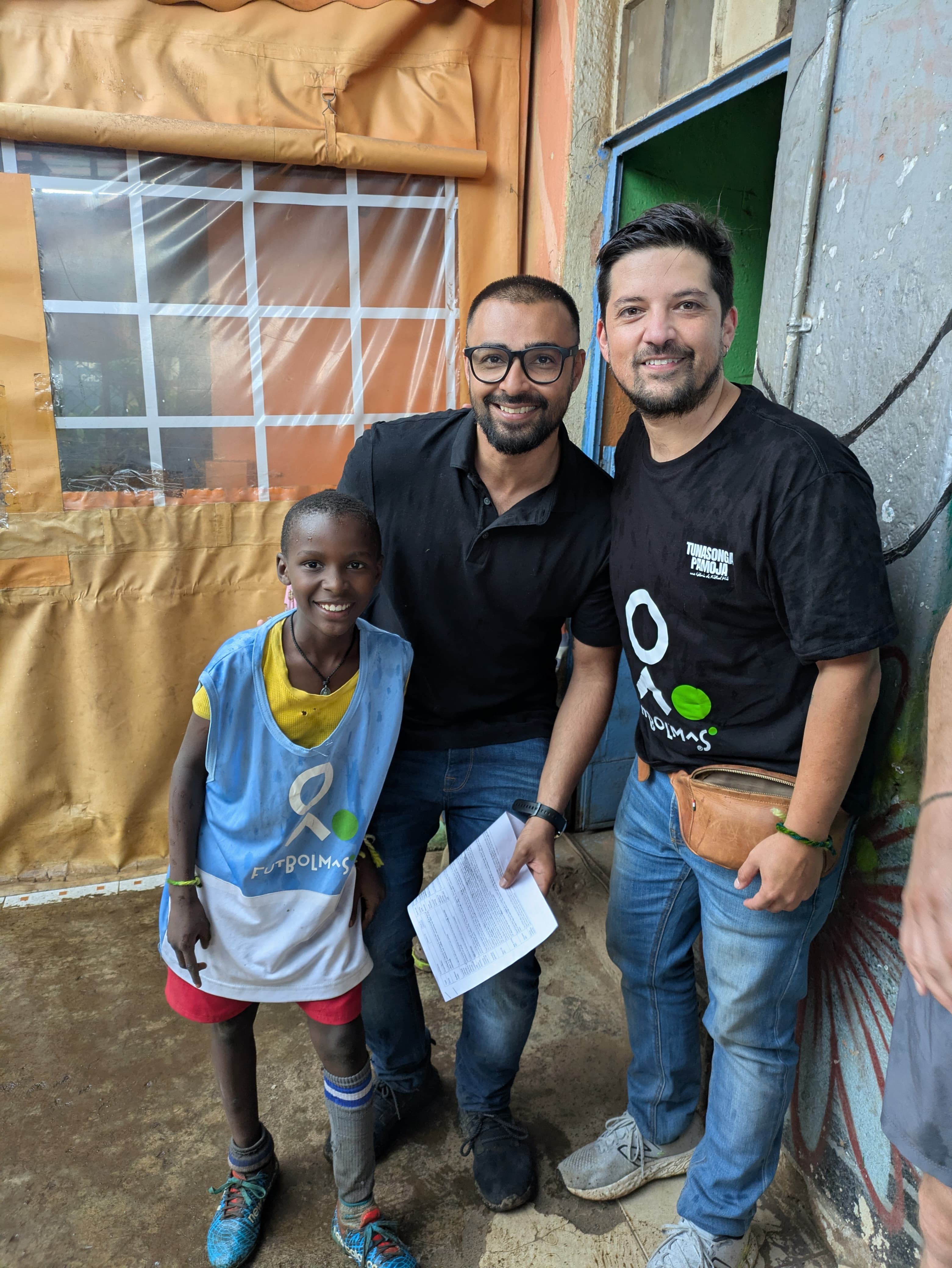

Victor and his friends started Futbol Mas sixteen years ago in Chile, believing that football can be more than just fun, that it can heal and build and refine the complex, irritable soul that we’ve been blessed with.

Today, Futbol Mas has its footprint in 14 countries and has deeply impacted over 100,000 children. Large numbers like that generally don’t impress me, because they are usually vanity metrics, making the intervention sound way more impactful than it actually is.

But, there was one stat that Victor shared that floored me – each child ends up getting about a hundred hours of training.

“We build these centres in different countries from the ground up, giving local leaders the autonomy to adapt the solution to local contexts,” continued Victor.

The sceptical side of me rolled his eyes and thought, easy to say, hard to do.

And then we visited the Futbol Mas Centre in Nairobi.

It was in Mathare, one of the toughest slums in Kenya, often overlooked in the shadow of the other big Kenyan slum, Kibera.

Us fifteen fellows from all over the world got off a fancy bus in the middle of this slum looking like fat pimples that attract all eyes all the time.

We walked into a room where the local Futbol Mas team presented their work to us. Victor, the co-founder, was in the room with us, but he sat on the side.

The Kenyan team talked about their work with pride, fielding questions, showing data on what was working and what wasn’t, and on how they had grown over the years to become a force for change in the hearts and minds of the most vulnerable children through my favourite sport.

Not once was Victor acknowledged.

Not once did Victor say anything.

Right at the end, the Kenyan Team Lead pulled out a photo and showed it to all of us. It was a photo from five years ago. A photo of him greeting Victor at the airport when he first visited Kenya to start Futbol Mas here.

And I wept.

They’ve always said “scaling deep impact” is hard, if not impossible.

And I’ve fought that notion, trying to brainwash myself that hard as it might be, it’s probably the only way to make permanent change, and nothing’s going to stop me from trying to do that.

But I was doing this with little proof.

Maybe I didn’t look hard enough, but when I saw what Victor and his friends had built, it gave me hope.

It gave me hope that deep impact can be scaled. It can be scaled de-centrally and globally, truly empowering local communities in a way that lights a fire to the notion that “empowerment” is a buzzword.

I cried because Victor was not the hero of the Kenyan Futbol Mas story; he was just the person who dropped the right pebble into the ocean. And in that, he had made his purpose bigger than himself. That’s the hardest stuff.

Dropping a pebble is hard because the pebble can’t be too small or too large. If it’s too small, the ripples die a quick death. If it’s too large, it overpowers the essence of why it was dropped.

Because in the end, it’s not the pebble that solves problems permanently, it’s the ripples it creates that do the magic.

Or at least that’s the fairy tale I believe.

*****

This little story might sound perfect, but it’s not.

Victor recently stepped down as the CEO of Futbol Mas. He said that he was going through a renaissance of his own, battling hallucinations plaguing his personal “life” which was so closely intertwined with his “work”.

Sixteen years can take a toll, but the fire within him isn’t extinguished and I know that, it’s just taking on a different shape.

I listened to him, half in a trance, half in my head, wondering if “work” and “life” are two separate things or not.

Lately, I have been thinking a lot about stress.

A certain kind of stress doesn’t scare me, it weirdly invigorates me.

I’ve chosen a stressful “job” that will necessarily generate stressors that need to be addressed. In these cases, stress is an excellent data point.

But then, there are unnecessary stressors that pop by occasionally.

Like a good friend you generally have a good time with, but these days, that friend just leaves you drained, and even more stressed out about things that don’t really matter.

Or like partying too hard, late into the night, having more to drink than you should, ruining your sleep cycle, and leaving you mentally challenged the next day.

Or like those folks that constantly seem to attract drama, leaving you wondering who the constant in all that is, and whether you’re a variable that’s about to get sucked into the vortex so you better run.

I’m realising that purging unnecessary stressors can be a superpower.

But it’s not easy.

Here’s to finding our necessary stressors.

*****

P.S. Gen AI was not used to write this, not even to "correct" it.

Cyclones

Our aunt, Bharti Masi, passed away last month, almost by choice.

My darling sister, a little rattled by all of it, texted me:

“Taking the decision to die because it’s better for you, I cannot imagine what Masi must’ve been going through.”

*****

Bharti Masi, one of my mother’s many little sisters, was born into a house mainly full of women and girls. Her mother, my grandma, was best described a little whack, but her grandma – Baa – was the stalwart of the house. A woman of strength and wisdom, unafraid and unabashed, loved and trusted. Universally respected.

Growing up, it almost seemed like Bharti Masi contested with her sisters on who was the prettiest of them all. The Katbamna girls were the talk of the town, a bunch of beauties to behold. My father and his brothers had hit a little jackpot, living in a tiny, rented space in the same building below these beauties.

And just as if intelligent design was real, the Bollywood script of the girl next door came to life. Bharti Masi’s elder sister became my father’s wife in a love story for the ages, still going strong.

Bharti Masi, on the other hand, would never get married.

Amidst all the beauty, what set Bharti Masi apart was her razor-sharp mind – unafraid and unabashed.

But at the age of 20, she was diagnosed with lupus, an auto-immune disease that can rampage through your body like a cyclone but still be “managed” with modern medicine.

The disease is death, but this ability to “manage” it seems like absolute psychological hell – unnecessary yet necessary. It’s as if the Devil is right around the corner, don’t tempt him to come around, but try as you may, he might just come along anyway and take it all away.

This constant fear of impending doom must be crippling, with the hope of survival serving only as salt on a wound that will never really heal.

When her body first attacked her at the age of 20, the entire clan – her family and her future family – came together to save her, quite literally. Her sisters and her brothers, and my father and his cousins all gave her blood, pumping life into her, in what now seems like a ceremony of kinship strengthened by tragedy.

She pulled through that first wave but was shaken.

She had lost her hair because of all the steroids but she gained a strong desire to conquer survival.

She tried everything to keep the Devil away, even engaging in Urine Therapy. She drank her urine every morning and saved some to massage her skin at night before falling asleep. The stench didn’t seem to matter – not to her, nor to the ones that loved her.

When people made fun of her baldness, she stripped off the scarf that covered her scalp in a rebellion that would be symbolic for years to come.

And then she fled.

She left for a land with seemingly greener pastures booking a one-way ticket to the United States of immigrants. She felt modern medicine might serve her better there. She went on to get her PhD in Audiology and became a tenured professor in a quaint little town in Michigan.

When I was 11, we all went on a family trip to Australia. She had come along as the ninth wheel with two families of four.

And boy, I hated her guts.

My rebellious eleven-year-oldness collided with her fearless reprimand. She always seemed to kill the buzz, snapping if the volume was too loud, pointing out all the dangers of a simple canoe and cutting through me with her stern scolding when I squeezed a ketchup sachet too hard.

I didn’t get it back then. And many others didn’t either.

She pushed away more people than she pulled in.

Our evolution doesn’t allow us to understand the depth of a person just by looking at them. Survival mechanisms are often masked by negativity and there’s no time to empathize with the rude, however broken, brave and beautiful they are underneath.

When I moved to the US for my undergrad, my mother forced me to reconnect with Bharti Masi. With my prefrontal cortex still figuring things out, I took it on as an errand to please my Mum, with an eyeroll or two that was still cool back then.

But the offshoot was a pleasant relationship. How can someone I used to fight with all the time ship me home-baked cookies across the land? And ever since, she followed my journey. Our relationship was punctuated with sporadic conversations and emails about plastics and photos and pain.

The more I learnt about life, the more I admired my Masi’s courage and the love that lay underneath.

It all started to make sense to me: she had been cursed with a deck of cards that had very few trumps, but she was a fighter. It was almost like all the trump cards she should have had, had slipped into the decks of people like me, and the Joker cards were replaced by the Devil. And yet, she kept playing.

While I made sense of all that unfairness, she battled with the senselessness of the condition she was a slave to.

In the years to come, the Devil kept showing his face – poking at her, and then going away and giving her hope, only to sneak back up again.

She would have some years of goodness, and then something would go wrong. Sometimes it was the disease and sometimes it was just sheer bad luck – like the time she slipped on ice outside her house and fell, breaking her arm that took ages to heal.

Then, a few good years later, she had a stroke which left her vision severely hampered, recovering slowly.

But she did recover from that, improved her already-great diet, retired from teaching and started embracing still photography while writing a cookbook. She seemed in high spirits and the final stretch seemed like a happy ending worthy of a Pulitzer.

Amidst all this rejuvenation, one day she found her arm had swelled a little. She delayed treatment because of the innocuousness of the swelling until it swelled more.

4 months later she was fighting for her life in the ICU. A couple of weeks after that, she died.

She died because that was the better option.

Almost all her main organs had failed but her brain and her heart were still churning. If she wanted to live, she would have had to be bedridden on a ventilator all her life, coupled with regular dialyses. Who wants that life?

“I don’t want to be a burden,” she said.

My mother could barely see her in that state. It’s too much pain, Anish, it’s too much.

Bharti Masi wasn’t alone when she passed away. Her partner, her best friend and some of her family were with her. No children though, nor any of the clan that had once given her their blood all those years ago. And that was that.

My mother says that she had many good years, but all I see is the unjust, uncontrollable tragedy of her circumstances, and her relentless courage to struggle through it right till death, with hope showing its worst face.

Maybe I’m being too negative about this. Or maybe, my mother’s love for her sister wants her to believe it was all worth it.

Who knows, my mother says. Who knows.

All I am certain of is that I cannot be certain about anything. And that as hard as I might try, I might not be able to make sense of everything.

I am not much of a quotes guy, but these days, this quote from the mighty Mr Chesterton keeps coming up:

The real trouble with this world of ours is not that it is an unreasonable world, nor even that it is a reasonable one. The commonest kind of trouble is that it is nearly reasonable, but not quite. Life is not an illogicality; yet it is a trap for logicians. It looks just a little more mathematical and regular than it is.

*****

As my mother and father mourned through this loss, I have been caught up in the cyclone that is social entrepreneurship. Just when I thought it couldn’t get more intense, it has picked up a notch.

The thing about cyclones is that people run away from them, even though that’s not what cyclones manifest for.

Entrepreneurship is pushing everyone you love away from you for "something bigger", “something bigger” that wise people don’t really understand.

Social entrepreneurship is pushing everyone you love away from you for something bigger, but the difference is that the wise people who love you fully understand this "something bigger", and that's almost worse. Because they won't stop you. Because it just might be worth it.

The ferocity of this cyclone has made me claustrophobic, running amidst different intensities of chaos while getting trapped in my own wind, without any space.

So much so that I felt it was time to move out from my parents’ home, in search of the eye of the storm.

With a little help from my sister, I told Mum and Dad that it was time to move out. Despite the grandiose gesture of “moving in with the ‘rents” a couple of years ago that garnered plaudits from the mothers of all my friends, my parents were as supportive as ever of this senseless retraction.

So much so that I wished that there was more drama. That they were angrier. So, I’d feel less spoilt. But that’s the irony of the support system I have, it’s almost senseless how supportive it is.

Even in the tough sport that is entrepreneurship, I feel spoilt. As a Shark mentioned on TV not too long ago: Anish, you’ve not gotten enough “dhakkas” (punches) in your journey.

While I make sense of this entrepreneurial cyclone that I’ve created for myself, my aunt, Bharti Masi, was born into a cyclone full of dhakkas. A cyclone she could barely make sense of. A cyclone devoid of any trump cards. Her last words were, “Modern medicine has failed me. Now go enjoy my money.”

But both these cyclones have one thing in common. They both seem to push people away. One has found its peace. The other is still searching for the eye, hoping that when it’s found, he has not pushed everyone away.

The Darker Side of Social Entrepreneuring

Last month, I was on my way back from a work trip in Stockholm. I was flying back via Dubai, where I grew up. Where my sister currently lives, with two darling little kids who I barely get to spend time with.

She said, stop by and say hi?

And I dismissed it rather quickly. It was stressing me out.

With work exploding, it feels like I’m constantly behind. A couple of extra days off after a week-long work trip would only push me deeper into the ocean of undone things that I was already drowning in.

I am really close with my sister, so it wasn’t an awkward conversation – she gets it and isn’t imposing in any way.

Which makes it worse. The ones that love you the most get it, and so you allow yourself to push them away just a bit more. Because they get it.

They get that you’re trying to do something different, something arguably important. But their unwavering support sprays a shade of entitlement onto your psyche. An entitlement that justifies compromise, sometimes unreasonably, creeping slowly into a weird sense of subtle, subverted narcissism.

The reason I gave my sister was that even if I came, I would be so distracted and distraught with all the undone things that I would end up feeling worse than not visiting.

Okay, she said. And that was that.

These days, I come home to proud parents. Proud, retired parents whose goal now more than ever is to support their child in his seemingly good work. Work that’s not some run-in-the-mill 9-to-5, but something that’s trying to make things better, something that allows pride to be contagious.

I come home late, exhausted and hungry. Mum has already texted asking me, when do you leave? so she can prepare ahead. A plate is already on the table and the food is already hot – twenty minutes later, my dinner is done. Dad doesn’t even allow me to take my plate to the sink.

In those twenty minutes at the dining table, I am generally grumpy, uninterested in updating them or anyone about anything, thinking about the hundred things that happened that day and the next hundred that need to happen the next day.

My father gets the major updates on my work by listening in on update calls with others – two birds, right? My mother is happy with a daily hug, which I sometimes forget.

There lies the irony.

For once, I have my darling parents so close to me and I still seem to be keeping them on the fringes – finding myself distracted in the name of the “greater good” while riding their pride, murmuring to myself I’ll fix it later.

And they never complain. Because they get it.

It really isn’t as simple as you’d imagine. The work we are trying to do is important. It is hard and grueling with unknowns that seem to grow at the rate of knowns but with the potential to result in deep, long-lasting systemic change. At what cost, though?

Then there's the investor world, sucking your soul, putting you through the wringer, and then ghosting you. I find it especially overwhelming when impact “patient” investors define impact and patience differently, often seeming more impatient than impactful while copy-pasting sharky term sheets from traditional investors.

Maybe, I’m being unfair or biased because these aren’t bad people – they’re good people with good intentions just doing things like they are.

The irony is that they first ask: what’s your unique selling point (USP)? and once they’re convinced of our uniqueness, they treat us like a homogeneous crew of social entrepreneurs.

A convenient flip of tone, a magical sleight of hand made easier by the classic power dynamic between the money-giver and the money-taker, exacerbated here in India by our deep-rooted paternalism and our “sir” culture.

I feel like I need to just snap out of it, but it’s not that straightforward. The work we are doing is hard and against the tide. It requires extraordinary effort to create the impact we want, and money plays an important role. But at what cost?

Amidst all this noise, I feel like I have to constantly remind myself of the true reasons I'm doing what I do.

This week, a former waste-picker who briefly worked with us committed suicide. He had been wrestling with alcoholism while his community seemed to both shun and support him. That’s how it is out there sometimes – ridicule for bad behaviour but always room for some support and second chances.

One of these second chances was working with us. He joined us at the beginning of the year and worked for a couple of months. He seemed to be doing well until he started coming to the lab intoxicated. After a slew of second chances and multiple stretches of unexplained absences, we had to let him go.

I remember asking him if there was a reason for his alcoholism, suspecting deeper psychological issues. We didn’t get much out of him, but he did once mention that he thought his wife was having an affair.

We don’t know anything for sure, but this week, on that fateful morning, he was drunk. He fought with his wife, physically abused her, and then hung himself, leaving behind two children – 10 and 5. And two widows – his wife and his mother-in-law.

Poverty is more complex than just income, jobs, health, and education. There is an entire obscure layer of psychological health that is rarely addressed.

The poor go through a lot more than you and me. They are probably more resilient than us because they have to be. But that doesn’t mean they are immune to psychological issues. In fact, often times these issues are masked by their poverty.

Last month, I gave a well-deserved raise to a top-performing colleague. And he broke down into tears. He has only studied till 10th grade and comes from a low-income background. While he has worked hard all his life, he just doesn’t seem to have gotten a break. Wiping his tears, he said this is the first time someone has truly valued his work.

And then I wept, multiple times, thinking how something as basic as valuing someone fairly for their work can mean so much – how low is this bar that we have set for ourselves?

These are hard problems we are working on. Does that justify me pushing my loved ones away a little? Does it make it okay to sell my soul to investors a little?

There isn’t a clear answer, but I generally find clarity in reflection.

What I know is that this is a long-term affair, and if I burn out too quickly, no one’s really better off. So maybe I can slow down a little, find the right investors partners without selling my soul and focus on building for the long run – all the while maintaining my sanity.

For which I need my loved ones.

And I probably need to get a tattoo somewhere that says: it’ll never be perfect.

Wardha, The Other World

He had taken the train from Wardha to Pune that week — his beloved wife was recovering from knee surgery, and he was obviously going to be there right by her side.

“Anish Beta, when are we talking? Her physiotherapy gets done at 4 pm so I’m free after that.”

My proud uncle had told him about the work that I was trying to do here in Pune, so he might have been curious. But I was a lot more curious.

I had read the only book he had written in English, Towards Holistic Rural Health, and I was floored.

For over forty years, Dr Ulhas Jajoo and his team of student doctors had served over forty neighbouring villages. It all started with basic health check-ups but evolved into something a lot bigger — the overall well-being of the rural poor while driving accountability and long-term sustenance.

But the most compelling part was how the team evolved its thinking.

They iterated on ideas sitting right alongside village folk, collected data, analysed it, charted trends and calculated ratios, conducted experiments, and then scaled interventions that actually worked to other villages.

And this started in 1978.

Before computers and mobile phones were common things. Back when they had to go village to village, person to person collecting data by hand, and doing old-school math on sheets of paper with pencils and scales.

Some decades later, as I sat across from him in Pune in awe, Ulhas Masaji was still more comfortable with his white A4 sheets, and his pen.

“Bol Beta, tell me about you.”

I said, “NO, tell me about you”. But he insisted, and prodded and poked and questioned and took notes on his white A4 sheets, unearthing the why of what I wanted to do.

And I remember thinking: this stalwart of good, bubbling with intellect hidden in the coffers of the non-English world, who had dedicated decades of his life to the poor, wasn’t forcing humility. He just embodied it. He was intrigued by the why of today’s youth, all the while drowning in the purpose of doing good work. Nothing else really mattered.

Those three hours with him were a whirlwind of emotions. As he tucked his pen back into the heart pocket of his self-spun Khadi shirt, he said, “Come to Wardha in December for this event we are hosting.”

And so, I went.

*****

Wardha is a small city close to Nagpur in Maharashtra. It’s somewhat famous because Gandhi spent a lot of time there after 1936, driving the last annals of the freedom movement. His legacy still radiates in the people who live there. People like my adopted Masaji, Dr Ulhas Jajoo.

For the last twenty-eight years, Ulhas Masaji and his family have hosted an annual event that spotlights individuals who have made a telling difference in India - the Tapodhan Shree Krishndas Jajoo Smriti Karyakram. You and I will probably not have heard of most of them because they usually toil in the non-English world, mostly outside of the spotlight.

They invite these heroes into Wardha and ask them to talk about their work, about themselves and what drove them to do the good they do. But what’s extra cool about it is that they also invite local, rural stakeholders to be inspired. It’s more than just some speeches.

For instance, this year’s theme was organic farming. On the first day, organic farmers from the Maharashtra region were invited to engage with the special guests who had oodles of experience sowing seeds sans chemical fertilizers. It was an intimate gathering that focused on depth and conversation and idea exchange — not only from the special guests but also among local peers.

The first guest was Vijay Jardhari from the hills of Uttarakhand. In the 1970s, he had taken part in the Chipko Andolan — the movement in India that inspired tree-huggers across the globe.

He told us about the time when he had held on to a tree to save it. A labourer, employed by the wealthy corporate folks who wanted these trees felled, came over to cut down Vijay’s tree. He resisted, so the labourer hacked at him, busting Vijay’s leg open. Blood flowing out, Vijay refused to budge.

Overwhelmed, the labourer muttered, “I came here to cut trees, not people”, and walked away.

As someone who has ridiculed tree-huggers in the past (both the literal and the metaphorical ones), I was being exposed to a different side, a perspective where I am more wrong than right.

The Chipko Andolan only sowed a seed in what would define Vijay’s main work for years to come.

He went on to start the Beej Bachao Andolan (Save The Seeds) — a grassroots, informal collective of farmers and activists working on saving indigenous seeds in the 1980s while most of Indian agriculture was being lured in by the Green Revolution. They did their own Dandi-march of sorts across Uttarakhand collecting and preserving some 350 types of indigenous seeds.

About 40 years later, the world is now realizing what Vijay intuited way back when — the importance of organic farming and indigenous seeds. Prescience seems to be a thing about people who drive real change.

Today, Vijay champions a holistic, multi-crop approach to farming, called Baranaj (Twelve Crops). Essentially, growing multiple crops is not only good for the soil but is also good for the subsistent farmer — the farmer should at least not go hungry.

Vijay strongly believes that Baranaj prevents farmers’ suicides, a plague rampant across rural agriculture in India. I remember him saying something along the lines of: if a farmer can always feed himself and his family, he might not want to kill himself.

I sat there, taking this all in, as Vijay’s high-pitched Hindi resonated right through my eardrum, deep into my mind.

At one point, Vijay, in the middle of applause and appreciation, said that all this good work was not because of him, but because of his fellow farmers from the hills of Uttarakhand, who no one really knows or talks about, because communication for them isn’t a top priority or a top skill.

As he said this with his hands held together in a deep Namaste, I wept and started to realize that my definition of humility was being redefined.

The second guest was Pandurang Shitole — a local hero of sorts in the realms of organic farming in Maharashtra. While I didn’t agree with everything he said, he was quite the speaker. His humour and intellect, interlaced with tingles of wisdom seemed to encourage (and delight) the organic farmers in the audience.

Ulhas Masaji strongly believes that one of the reasons our farmers struggle is that they’re not really good at selling in the modern world (i.e. at marketing). One reason to bring Pandurang to the foray was to have him share his experience in the art of selling and business. He also encouraged the organic farmers in attendance to create an informal collective of sorts, a collective to share ideas and work together to make everyone better off.

The next morning, they did just this. It was satisfying to eavesdrop on their conversation that brought together varying perspectives, as the old and the young, the fully-organic folk and the partially-organic folk tussled it out, largely respectfully.

The evening saw a more formal affair come to life. The two special guests adorned a stage in front of a larger audience of about 200–300 folks from Wardha. They recited their stories again, although this time, it was a bit shorter, interspersed with Indian classical music dedicated to their work.

It was an inspiring weekend, a weekend that only a few years ago I wouldn’t even be able to imagine, let alone experience.

And deep underneath it all, there was a thread of pure, loving energy that engulfed everything.

This was a free event with no checking of tickets, where all invitees were fed wholesome breakfast, lunch, high tea and dinner. The “caterers” were not caterers — they were like family, cajoling and serving us with love and energy, until saying no felt almost criminal.

The Jajoo family were giving with all their heart, hosting us like we were their children. In some sense, we all were.

As much as I am Indian, I come from a different world.

A world where intellectualism and complex ideas are only communicated in English. Where self-proclaimed effective altruists and “change-makers” analyse problems and hypothesize solutions in fancy PowerPoint presentations while sitting on golden thrones. Where using complicated philosophical jargon and mushy data is enough to direct impact. Where true immersion in the lives of the downtrodden doesn’t seem to be required — no, a week doesn’t count, nor does a year, especially if you can’t speak the language or connect deeply with their culture.

This other world that I saw in Wardha was enshrined with real work, real love, real dedication, real immersion, and I cannot help but think that some of it are lost in translation to the rest of my world. It’s not like this other world is perfect. It has its own issues, where the barriers of language make it harder to access the latest research from around the globe. Where speed and time have different meanings. Where technology can be a hurdle that discourages leaping, anchoring it to a past that might not have all the answers.

So, I can’t help but think that true magic lies at the confluence of these two worlds, where both prosper on the back of each other.

And that’s the confluence I want to embrace, as I oscillate from my world to the other.

This is all just to say that I feel like my veil of ignorance is lifting.

*****

Just when Wardha couldn’t give more, it did.

On our way back to Pune, Dad said we should stop by the Vinoba Bhave Ashram and meet Gautam Bhaiyya.

I imagined Gautam Bhaiyya to be not-so-old, but it turned out he was almost eighty and toothless. Mum urged him to put on his dentures, and then he suddenly seemed a lot younger, with apparently a more familiar smile.

And then he started speaking, still as razor-sharp as a precocious twenty-year-old, going back to the days Mum and Dad had spent with him, how my grandmother was close to him and how he spent a lot of time with Vinoba Bhave.

Now for those not acquainted with Vinoba Bhave, he was a close confidant of Gandhi while being a savant of sorts, speaking many languages, and contributing significantly to the freedom struggle in the 1900s, leading up to our freedom. He was sort of a big deal.

So, when Gautam Bhaiyya said he had spent a lot of time with him, I got curious. What do you mean by “a lot”?

Gautam Bhaiyya casually said that they — Vinoba Bhave and him and other folks — went on a thirteen-year yatra around India on foot, asking for land donations from the upper classes and transferring them to Harijans or low caste folks who were landless. The movement was called Bhoodan.

And the numbers are staggering.

4.4 million hectares of land were donated by 1.8 million people across India. This land was donated to 1.2 million Harijans in what must be one of the greatest voluntary transfers of wealth. And I can’t imagine how many generations of families it has permanently lifted out of poverty since then.

This obviously didn’t curtail my curiosity. When did this happen? How?

The journey started in 1951 when Gautam Bhaiyya was 13 years old. He asked Vinobaji if he could come along, and Bhave said yes — simple as that. He also happened to have a camera with him, a rare thing back in the day, and the pictures he took then are priceless.

As priceless as the book he gifted us on our way out — a picture book he had put together of Vinoba Bhave’s life — photos from his childhood, his encounters with Gandhi, the thirteen-year yatra and his last years.

Gautam Bhaiyya had stayed with my parents in England in the 1980s when he was visiting there to give a lecture in the House of Commons. Ever since, they shared a special connection, a bond that can only be explained by their innate comfort in each other’s presence.

And there I was again, overwhelmed by everything.

Overwhelmed by the audacity of a thirteen-year-old to accompany a legend on a journey that changed so much — without money, with only will. Overwhelmed by the deep-rooted relationships my parents had sown, which decades later still seemed as ripe. Overwhelmed by the work that has been done to rebuild this country in a short 75 years.

All the while, ready to continue building.

*****

Moving Back In With The ‘Rents

I remember when I was eighteen, I couldn’t wait to get out of my Mum and Dad’s house and be free, be independent, and “become a man”.

And I did, I flew.

I flew out to the United States of immigrants for my undergrad and thought I would never look back – here’s to never living with Mum and Dad again. I was excited to live by myself, at my own beck and call, without the loving heckling of my parents.

The “loving” part here is key. There was no trouble at home.

My parents were and are awesome.

They found the right balance between letting me be and making sure I didn’t veer off the “right” path. They were strict but fair, putting me up on a pedestal only when I deserved it. And when I didn’t, encouraging the punishment I deserved, without ever making me doubt their love. I was a naughty kid.

They were protective but reasonable. I remember in tenth grade I bullied them into sending me to the UK for a football training camp for ten whole days. The important part was that I wanted to go alone. I had to go alone, and I wouldn’t have it any other way. Fine, said the father, but do some research first, and make sure you’re getting a good deal.

My parents were always ahead of their time. They saw the value in looking at education from a more global perspective, encouraging me to switch to IB even before I thought it was cool. But Dad, I want to be Headboy in this school. Okay they said, and no, I didn’t become Headboy.

It also helped that Dad was a sexologist on the side. When I was about 14, I remember him asking me to make a PowerPoint about testicular cancer. He said, Anish, should I call it “Know Your Testicles” or “Know Your Balls.”

And I looked at him a little bewildered, thinking I rather not know anything about this.

But you know what, later, when we had “the talk”, it went from awkward to comfortable at lightning speed.

There was no official Sex Education in Dubai, where I grew up. To solve for that, I only recently found out that they used to intentionally leave Sex Ed books lying around in “convenient” locations so that I could happen upon them when they weren’t around. And yes, I did happen upon them, and so did my friends. Friggin’ geniuses.

Both my parents are doctors and have served people all their lives. Despite that (and them being Indian and all) they let me go to the US to study Sports Management. Yes, they were okay spending their hard-earned money on Sports Management.

They have always believed in me. And believed that I should pursue what I believe in. I look back at it now and wonder if they hadn’t let me study Sports Management (my “passion” back then), I would have always carried a level of resentment with me. Three months into the program, I realized it was a waste of money, and swiftly enrolled into the Business School.

When I left for the US, my mother got a rash on her back. When she went to the doctor to get it checked out, he said it was probably because her son had just left home. I never learnt about this until much later. And I remember right then, during my first winter vacation in the US, I chose not to go home to see my parents, because hey, I spent the last eighteen years with them, that’s enough.

I saw them only once or maybe twice a year while I was abroad. And I always made it seem like it was a big deal. Maa, I’m busy, work’s crazy, I don’t have the time.

I have only recently realized that I will never have enough time with Mum and Dad.

At my rock bottom, when I was working in New York, they visited. I was lost and depressed, unsure about who I was and what I wanted to do.

I will never forget that conversation we had in Fort Greene Park. I had a good job, was making great money, my company had applied for my Green Card, but all I wanted to do was quit. And do something “better”. But was it worth giving up this life I had that almost everyone dreams of?

I remember explaining this to them – distraught, confused, lost, looking to them for some sort of approval, some sort of a push while trying to mask my shame.

What I got back from them was clarity. It’s time, they said, to quit and do something better.

My parents, who don’t come from much money, who have worked their butts off to make money so that my sister and I could have a more comfortable life, were telling me it’s okay to just give this continued, guaranteed “success” up to pursue something “better”? No drama? No confusion? No apprehension? Anish, what’s the worst that can happen, we are here na.

It has been the most pivotal decision I have made – quitting. And it has been the best thing that has happened to me so far. Ever since, I have found contentment in purpose, and in work that I feel really matters.

All the while, my parents have cheered me on, from afar but still somehow always right there next to me, especially when it matters most.

Besides literally creating me, I can’t stress how important they have been in shaping me, and in empowering me to be the best version of myself, without expecting anything in return, besides maybe a phone call. I will forever be grateful.

They’re almost 70 now, about to retire. They want to remain forever young, but no amount of hair dye can hide that they are getting older, a little tired.

Retirement was always going to be in India. For twenty-five years, Dubai has been great to them, but never home. Home was going to be Aurangabad, until I moved to Pune. Ma, Dad why would you move to Aurangabad if I am in Pune?

They said, Anish, you never asked.

And there’s the irony of it all. My parents have raised their children to never ask anyone to do anything they don’t want to. To be independent. To serve. So how could I ask my parents to move to Pune just for me? Turns out they were thinking the same.

This infinite loop of misunderstood love is the most drama there has been, at least so far. And I hope it stays that way.

Fifteen years after I left my Mum and Dad’s house, I have now realized that home is where the whole is. And as they retire into their last chapter, I rather be nowhere besides right next to them, back at home.

*****

Entrepreneuring

The toughest days so far have not been the longest ones. They have been the ones filled with anxiety. Where control seems like an illusion. Where uncertainty paralyzes progress, and all you can do is wait, while anxiety engulfs the depths of your cranium.

Our biggest investment — the magic machine — is more than a month late. It’s been four months since we placed the order, trying our best to plan ahead, hoping foresight would hedge hindrance.

But there’s only that much you can anticipate. Only that much you can control. Which doesn’t mean nothing is controllable, just that all you can do is direct the sailboat in the right direction, and hope it catches wind.

In the larger scheme of things, it’s really not the end of the world. And that zoomed-out perspective is important, because day-to-day, everything seems important.

Everything about my enterprise seems important. Everything outside of it seems irrelevant.

I feel like my life has now become supremely one-dimensional. There’s no time for new friends, or new adventures, or travel logs, or a new TV show. The idea of dating seriously seems like a nightmare of commitment that I know I’m going to fumble. The idea of keeping plants in my house feels like pressure I don’t need — I don’t want them to die. My weekly work wardrobe is now monotonous and comfortable, so I have one less irrelevant thing to worry about. I am balding, mainly because of my genes, so, much to the shock of my darling parents, I’m trimming it away, which saves me from doing one more thing after my morning shower. I have given up meat because of the hypocrisy it reeks in relation to the work I do. Comfort seems like a trap.

I know this sounds like a prison of sorts, but the irony is that its self-designed and intentional. I crave rhythm so that my conscious deliberation can be focused on the tough, complex problems I have chosen to solve, while minimizing inconsistencies along the way that foster self-loathe.

And I am friggin’ loving it.

I am finally reaping the contentment of delayed gratification.

Ever since I quit the corporate rat-race to pursue purpose, I have been building up to this. And it all seemed dreamy in the beginning, but the work has been put in, and some four years later, the seeds are bearing fruit.

But there’s still a long way to go. I barely even consider myself an entrepreneur. Yes, we have built and we are building, but we haven’t really changed anyone’s life yet, or even sold anything for that matter.

The unfair advantage of having risk-free capital has made the journey so far infinitely simpler. We have had the fortune of early breakthroughs and minimal setbacks, but we don’t even have a product yet. We need the magic machine for that. It’ll be here in a couple of weeks. Maybe.

So yes, plenty of entrepreneuring left to do. And hopefully, that never changes.