Anand Giridharadas is an alarmist. Of the good kind though.

He spends about 300 or so pages in his new book dismantling the whole concept of how we perceive “doing good” and “social impact”. He systematically calls out a laundry list of people, organizations and concepts that have attempted positive change. This list includes social enterprises, impact investing, foundations run by rich capitalistic, oil-producing, hedge-fund managing “philanthropists”, “thought leaders” such as Adam Grant, Simon Sinek and Thomas Friedman, the Gates foundation, the Rockerfellers, B Corps, the Koch brothers (no surprise here), almost everything about the Clintons, the Aspen Institute, Uber, Summit at Sea — basically all of Silicon Valley — and most importantly, himself. The fact that he includes himself in the list is why we should all be listening and evaluating and changing.

The Book

Anand’s premise, in a nutshell, is that the Utopian idea of “win-win” in the social impact space is just that, Utopia. He believes that despite all the above-mentioned elites spending the best part of the last 30 –40 years trying to “do good” while also making money, there still exists an incredible amount of inequality of income. In fact, the data says that since 1980, in the United States, despite all the “great” work of philanthropists, foundations, social enterprises and impact investors, the richest 10% of the population has doubled their average pre-tax income and the richest 1% has more than tripled it. He argues, boldly and fairly, that social good in today's world is a form of moral licensing — “I have donated a couple of mil to charity, so that makes it okay for me to continue drilling oil wells.” He argues that these elites, talk about doing more good instead of doing less bad, and live in somewhat of an echo-chamber, justifying their daily cake by giving a few crumbs to the less fortunate. They claim to want to change the status quo without really changing the status quo, without sacrificing their luxuries.

–40 years trying to “do good” while also making money, there still exists an incredible amount of inequality of income. In fact, the data says that since 1980, in the United States, despite all the “great” work of philanthropists, foundations, social enterprises and impact investors, the richest 10% of the population has doubled their average pre-tax income and the richest 1% has more than tripled it. He argues, boldly and fairly, that social good in today's world is a form of moral licensing — “I have donated a couple of mil to charity, so that makes it okay for me to continue drilling oil wells.” He argues that these elites, talk about doing more good instead of doing less bad, and live in somewhat of an echo-chamber, justifying their daily cake by giving a few crumbs to the less fortunate. They claim to want to change the status quo without really changing the status quo, without sacrificing their luxuries.

Anand does this with a flurry of examples and facts, without being afraid of even calling himself out, let alone his friends. He takes a whack at understanding the cognitive dissonance that some of the elite enslave in their heads but do little about. He spends little time on proposing a proper solution, but that’s not his goal — his goal is to unearth the roots of the problem, and he mentions that intent, albeit somewhat indirectly. When he does talk about solutions, he argues that some people (the rich) need to lose or sacrifice something for the less fortunate to win. And he believes this can only happen by changing the “system” — that is by changing policy and law, in place of putting band-aids on the current tax-haven-y system. In a couple of words, his solution is better government.

My Head

While reading all this, I went through a rollercoaster of emotions — from wanting to hiss at him for trying to dethrone some of my core beliefs to wanting to hug him for his brave but tactful dismantling of the powerful. I believe in social enterprise. I believe that some sort of win-win is the only scalable, sustainable, long-term solution. I believe that the private sector has a role to play in solving today’s biggest problems. This book was the first thorough attack on these core beliefs of mine. So, until the very end of the book, I did not know which way I would lean — does he have some sort of glory-seeking duplicitous agenda? Or does he actually have a point underneath it all?

What sold me was his acknowledgements chapter. In probably one of the best acknowledgements I will ever read, he convicted himself as being very much a part of the problem. He was complicit, guilty. But, being a part of the problem is the best way to diagnose it and understand it. All he needed to do was find the courage. And he did. It started off with an off-topic speech at the Aspen Institute conference and has boiled into this book. He just told these emperors that they are not wearing any clothes.

So gallant, and I am so a fan.

My Take

Having read, absorbed and said all that, I still believe in social enterprise. I still believe in the power of the private sector to contribute towards systemic change. I also believe in having difficult conversations. I believe that criticism is an absolute necessity for growth. I believe that understanding all sides of an argument is crucial for progress.

So Anand, here is my take.

I am not going to argue against your argument on foundations, philanthropists and thought leaders — I agree where you are coming from and frankly don’t know enough to warrant a strong opinion. The only portion I want to argue for is social enterprise. The devil is always in the details and when it comes to SocEnts, that detail is the definition. For me, a social enterprise exists solely to solve a real problem and uses a financially sustainable business model to solve and scale it. It is profit-seeking to reduce dependencies on donations, grants and other one-time indirect revenue, but it is not profit-maximizing. A true social enterprise is tested when it needs to decide between maintaining its impact and increasing its margin, and in this “or” case, it will always stay true to impact. At this point a whole bunch of arguments are probably exploding in your head — what is a “real problem”? What do you mean by “impact”? Definitions are theoretical so can this “social enterprise” really exist? Isn’t “social enterprise” just a band-aid?

The biggest issues faced by the social impact space is defining impact / “real problems” and measuring impact / solutions. This can be a slippery slope, so for the sake of this argument, let’s settle on the 2030 SDGs set by the UN as the real problems we need to solve. They are not perfect, but I think they are the best we’ve got, and it is important to have a central body align as many people in the world as possible.

“True” Social Enterprises

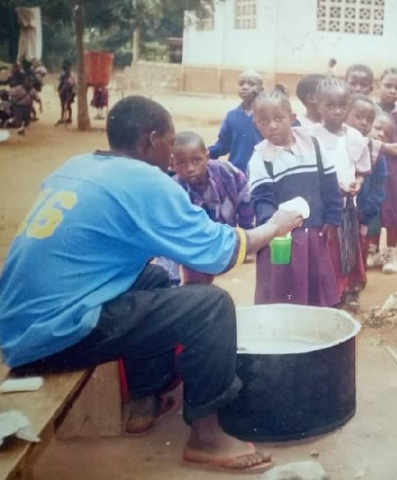

Can these social enterprises really exist? Yes, they do exist. Samasource exists to fight poverty by creating meaningful “microwork” while simultaneously providing vocational skills. Upaya Social Ventures is focused on ending extreme poverty and is trying to do so through job creation. They spend as much as 10% of their expense budget on impact measurement (which is high), and no, they are not doing it for their board / investors, but they are doing it for self-governance. Financial return is very much secondary. Babban Gona is catalyzing small farmers in Nigeria with a goal of securing the country’s economic future. Husk Power Systems converts rice husk into electricity in a financially sustainable way, and lights up homes across India and now, even across parts of Tanzania. Algramo is battling the “poverty-tax” in South America by providing necessities like rice, sugar, chickpeas, detergents, etc at a lower cost to the rural poor. EduBridge exists to fulfill the “skill gap that exists currently between semi-urban/economically backward youth and the skill requirements of the high-performing companies/government organization” in India. Yes, these are just six examples of true social enterprises, and you could argue that there are plenty of so-called “social enterprises” greenwashing their way to sizeable financial returns and not actually making any significant impact. But my point is less around how many of these currently exist and more around how many of these should exist.

Public + Private

The other question that might have popped up in your head is — fine, these social enterprises are doing good things, but how are they changing the system? As I said, I don’t know if the majority of social enterprises are “greenwashers” or “true” social enterprises, but that is not where the crux of my argument lies. I believe that systemic change needs both the public sector and the private sector to play its roles. I agree with you on the importance of policy, government and taxation, but I also feel that policy needs to be significantly supported by social enterprises that can help foster and scale significant systemic improvements. Steve Case also talks about it in The Third Wave where he stresses the importance of policy and partnership along with the traditional elements of people, perseverance and passion to carve success in the next chapter of innovation. Yes, you probably include him and the Case Foundation in your list of complicit elites, but that doesn’t mean he doesn’t make sense.

“Win-Win” Can Exist

This also comes back to your “win-win” argument, and again definitions matter. If win-win is defined as making millions of dollars and then trying to also simultaneously donate some of it towards a vague definition of impact — like you, I am not for it. But if win-win is creating social impact with a financially sustainable and responsible business model, then I am all for it. In fact, I think this win-win exists and can flourish. You can fight me on what I mean by financially sustainable at an individual level. But, without going down a slippery slope, I think the effective altruism movement does a fair jobquantifying the level of income needed to be “happy.”

Inequality vs Poverty

To keep with the importance of definitions, I think it is important to highlight the difference between inequality and poverty. I don’t think poverty is a euphemism for inequality. To me, you could end poverty but still have inequality, and theoretically that does not have to be a bad thing. Yes, a lot of today’s poverty is driven because the rich exploit the poor, but that does not have to be the case. In a merit-based society, you could have a just, but unequal economic competence hierarchy. As Jordan Peterson constantly cites, hierarchies (competence and / or dominance) have always existed in humans, and are important to incentivize progress. So, I think definitionally, inequality will always exist and should exist to a certain extent. If we build the right societal structures through policy to ensure that inequality is not driven by exploitation but by meritocracy, the economy could start to sing.

Bringing It In

To tie all this together, yes seismic changes need to be made in the public sphere, even if that means more taxation, and negatively impacting the richest of the rich. But those systemic changes need to be corroborated by an impact-centric private sector which allows solutions to scale — we need to find that fine balance between the public and the private sector, and switch to doughnut economics when it comes to measuring economic progress. Income inequality will not and should not go away, but poverty can and will. What’s important is to ensure we live in this imagined society of ours giving everyone equality of opportunity. But equality of opportunity does not equal equality of outcome.

Thank you, Anand, for finding the courage to write this book. It took me on an emotional and intellectual journey full of twists and turns. I want to be a social entrepreneur, so this seriously challenged my way of thinking. But once the dust settled, I think it has made me more conscious of the importance of systemic change to fuel overall economic and social progress.

Maybe that is why it is important for you to be an alarmist. It is important for someone to push the guilty to the other extreme, and maybe then, they will land somewhere in the middle, which is maybe where you exactly want them to be.

I might be projecting. I might be being naïve and rationalizing because I need some concept of a win-win to exist. But, I am trying to be as conscious of my bias as possible, and hopefully that will help me keep it real when the rubber meets the road.

P.S. Can’t wait to hear you speak at SOCAP18.

ripping off brands that don’t really align with the transportation industry (found one with the Playboy bunny once). They are almost creative masterpieces of art. They are also notorious for their need for speed around the mountains of Guatemala, feeling sometimes more like over-stuffed roller-coasters without seat-belts. So yes, it can be thrilling if that is your thing. And oh, they do get robbed occasionally, and drivers have been killed by gangs to facilitate a successful heist of the rest of hapless populous in the bus.

ripping off brands that don’t really align with the transportation industry (found one with the Playboy bunny once). They are almost creative masterpieces of art. They are also notorious for their need for speed around the mountains of Guatemala, feeling sometimes more like over-stuffed roller-coasters without seat-belts. So yes, it can be thrilling if that is your thing. And oh, they do get robbed occasionally, and drivers have been killed by gangs to facilitate a successful heist of the rest of hapless populous in the bus.