A Bridge For Change In Tanzania

Ocheck Msuva’s story needs to be heard.

Rejection

Ocheck’s existence began with rejection. When his mother found out that she was pregnant, his father refused to accept her pregnancy. He was born much to the chagrin of his family, who lived a poor life in rural Tanzania. So much so that Ocheck was sent to live with his aunt. His aunt gave him shelter but never took him as one of her own. When you don’t have much in this world, even blood isn’t enough to warrant love.

The first time Ocheck tried to kill himself was when he was twelve. Early education is technically free in Tanzania if you can pay for your own uniform, supplies and examination fees. His aunt refused to buy him a uniform for school, espousing the burden of taking care of Ocheck in addition to her own children. And this was the final straw. If nobody wanted him, why exist? He found a tree, and some rope. While trying to setup this killing contraption, some people happened upon the tree. Scared, he ran.

The second time Ocheck tried to kill himself was when he was fourteen. He had stolen a uniform from a neighbour so he could somehow make it to school. But after dragging on for a couple more years, life still did not seem worth it. This time he found some pills. But fortunately, or unfortunately, they weren’t enough. Fate can be cruel to even the most innocent. Belonging is how humanity has survived and thrived through the ages, and to deprive a child of it at his most malleable and vulnerable time is to give him no reason to live.

Hitting The Streets

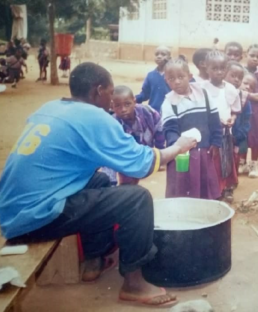

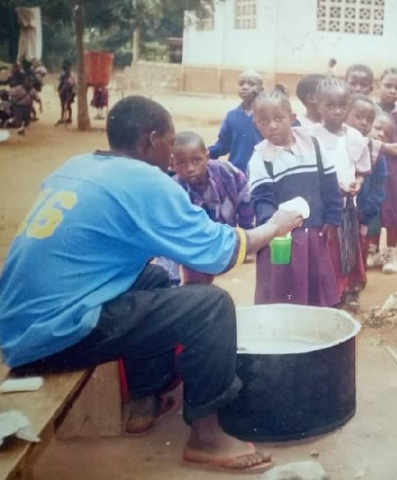

At fifteen, Ocheck felt that enough is enough. It was time to try this “life” thing on his own. He dropped out of school and ran away from his aunt’s place to live on the streets of Iringa. The streets bought him a little more luck. He found small jobs to survive. He cooked meals for kindergartners and at one point, even opened his own little street stall that sold fries outside of a church. He saw wealth, not his own, but of his rich employer who he worked for as a house boy. He once told the wealthy man who employed him that he dreamed of going to university and becoming someone. To this, he replied, “If a foolish person says stupid things, I normally do not listen.”

This crushed Ocheck. But his takeaway was that even the wealthy can be miserable. And early on, despite not having anything, he learnt that maybe money doesn’t bring you happiness. Through all of this, Ocheck still held on to a dream. And as cliched as this sounds to us, that dream of being someone, standing for something and belonging, is what kept him going

.

A Dream

Done with the street hustle and with a little money in his pockets, Ocheck went back to school. He started focusing on his classes and his scores rose. He spent his Sundays as a pastor, preaching and singing in the local church. His excellent grades got him admission into the University of Dar Es Salaam, and he took on a loan to fund his bachelor’s in political science there. Slowly but surely, Ocheck finally found his rhythm and his dream of becoming someone started turning into reality.

During and after University, Ocheck scored some well-paid gigs courtesy of the seeds he had sowed earlier. This gave him a bit of money and the gears in his head started turning. He realized that there were thousands of kids like him who had been discarded from their families and had nothing. He realized that there were thousands more whose dreams had withered away because reality was just too real. Ocheck believed that the only reason he survived was because he had a dream. And against all odds, he made his dream of graduating from University and of becoming someone a reality. He believed that if he could give the youth of Tanzania the power to dream again, and the encouragement to give their dreams a chance, he could instigate real change in Tanzania. So, in 2015, with the bit of money he had saved up, instead of looking for a comfortable, well-paid job, he decided to start Bridge For Change.

Being The Change

Bridge For Change (BFC) was created to empower the youth of Tanzania through training sessions, career support and mentoring. It blossomed quickly. Within three years, it had impacted over 18,500 students across 38 schools, and had mentored over 600 students at a deeper level while working with the likes of UNICEF, Vodacom, The Goodall Foundation and Cambridge University. BFC held “dreamscaping” sessions where school students were encouraged to draw out their dreams and then to find a path that took them there. And in the middle of all this, stood the inspiration of Ocheck — a testament to the fact that despite the gravest of odds, it only takes a dream to garner hope and strive towards the seemingly impossible.

In mid-2018, Ocheck started to feel that something wasn’t quite right at BFC. They were growing and making impact but were wildly dependent on their donors. What they were doing was not scalable. It felt like all that was important was ensuring that their donors were happy and that they were hitting the ambitious impact numbers demanded by them. There seemed to be ample width but not enough depth. All this made Ocheck hit the pause button and re-evaluate what the right next step for BFC was. And that brought him to Nairobi.

When I Met Ocheck

I met Ocheck in Nairobi as a part of the Amani Institute program. He was a fellow there trying to figure out where BFC needed to go and I was a fellow there hungry to learn by working in the social enterprise space. We couldn’t have come from more different backgrounds. While Ocheck’s aunt was looking for ways to get rid of him, any of my aunts would have adopted me in a heartbeat. I was blessed with an incredible family that pushed me beyond my limits. I didn’t need a dream to survive, instead I thrived on the fear of not making my dreams a reality — I had it all, how could I not?

Ocheck’s story is compelling but what sealed it for me was his ability to face the brutal facts. He told me that there are some significant systemic issues in the education system in Tanzania which severely impact the productivity of their youth. He said that they need to stop pretending that the solutions can only be found in Tanzania. “What’s important is that we find the best solutions for our youth, irrespective of whether it is from inside or outside of our country.”

This honesty struck a chord. Half the world talks about the “white saviour” issue engulfing most of Africa, and here you have a Tanzanian, who has been to hell and back, who is willing to put his pride aside and is committed to finding the best solution for the problem he has himself struggled with, irrespective of whether it comes from a Tanzanian or a “white saviour.”

Ocheck had enrolled in the Amani program looking to transition BFC from a typical non-profit to a more financially sustainable social enterprise. That’s where I saw an opportunity to add value. The Amani program allows fellows to pair up and work on projects together. This project was real. Ocheck was real. So, I started making my case, and he bought in.

In the next four months, we stripped down the organization and started to build it back up. We re-evaluated the extent of the youth productivity problem we were trying to solve in Tanzania and the numbers were glaring. We juggled ideas ranging from trying to create jobs by catalysing wheat farming in rural Tanzania to formalizing the informal real estate labour force. We finally settled on something less ambitious but more realistic. We didn’t want to part with the ambitious ideas though so we put those aside under the label “eventually.”

It was not all hunky-dory. Ocheck and I have different skill-sets with different working styles from different cultures. I am almost infested by the hustle and bustle of maximizing productivity from my Corporate America days — low in patience, high in productivity. Ocheck embodies a different kind of hustle, one filled with patience and persistence. I brought in the Excel skills, the PowerPoint skills and the strategic structure that has been chiseled in my DNA, while he brought in the local context, the history, the commitment and the direction. I didn’t pretend to know anything about Tanzania and the Tanzanian youth and Ocheck didn’t pretend to know anything about Finance. We played to our strengths while respecting what each brought to the table.

It was still frustrating in parts. My expectations skyrocket for those I admire, sometimes beyond reason. At times, I was hard on Ocheck, really hard. But he took it like a champion. I have never seen anyone take feedback as well as he does. There was a genuine desire to grow and he bloomed — and that’s in line with the research that’s out there — surround yourself with people who can give you objective hard feedback; our minds are too adept at rationalizing even the most obvious shortcomings.

Reflection

All this made me reflect deeply. There I was, coming from an extremely privileged background, with the audacity to berate for unreasonable expectations. What right did I have to do that? Yes, the past doesn’t matter when you’re in the present, but you can’t discount it either. I have spent my entire life educating myself in the most privileged schools, never worrying about a meal. Ocheck’s history is different, and that matters. The grit he has exuded to make something out of nothing is something I can never fully comprehend. His courage to invest the little good fortune he got into becoming an entrepreneur is something I will never be tested with. He has his skin deep in the game that he has dedicated his life to winning. He serves as an inspiration for me like none other. To never give up. And for that, I could not be more grateful.

After the Amani course, Ocheck invited me to Tanzania to run a couple of sessions for BFC. I had the privilege of teaching human-centred design to about fifty university students and running a mini-training session for his team on learning how to learn. I probably learnt more from them than they did from me. But more importantly, I got a glimpse into Ocheck’s world. I got to see in-person what Ocheck had been talking about — there is a gap in the Tanzanian education system that needs to be bridged. I also got to see the admiration Ocheck has won from the people around him. He might not have a family, but one Saturday morning, some of the brightest minds of Tanzania — PhDs, engineers, UN fund managers — showed up on their own stead to brainstorm ways to improve the productivity of Tanzanian youth. And they showed up for Ocheck. Not only because of who Ocheck is and what he has done, but because of what he stands for. As much as this is Ocheck’s story, what makes me believe in him is that this is not about him, this is about something bigger.

And that’s what I have bought into — what he stands for. When we accepted our differences, there was something magical that developed in the way we worked together. There are powerful synergies if you can learn how to combine local commitment with foreign expertise. So while the “white saviour” complex is a thing, there are ways to work with committed local leaders as long as you’re willing to not pretend you know everything and drop the ego.

There is still a long way to go for BFC. It has not been easy, and it is not going to be easy. But after what Ocheck has pulled through, this might be more of a cakewalk.

Humility

I remember one morning in Nairobi, when Ocheck and I were walking to class, he said, “Anish, I really want to forgive my father, but I don’t know how.” This is the same father who refused to acknowledge Ocheck as his son for the first twenty years of his life, who threw him out of the house to fend for himself. I didn’t know what to say.

In Tanzania, Ocheck was adamant that I visit his house — a little studio which my one month of rent in New York could cover almost six years’ worth of rent for. He said, “Anish, in Tanzania, as a guest, I must host you at least once. And yes, this place is small, but my landlords treat me like a part of their family.” He pulled out a photo album and walked me through his past. There was a photo of him as a cook serving little kids while he was on the street. There was one from when he had built his own little street stall that sold fries. There was another of him as a house boy. Another as a pastor, one of him singing, one of him during his graduation, and a few more that he had somehow managed to hold on to. There were no pictures of him before the age of fourteen. And to think, my little one-year old niece already has thousands, enough to fill a truckload of photo albums.

Despite everything, there is immense joy in Ocheck. There has been nothing simple about his life, yet he lives simply. He is not perfect but he champions humility, grit and faith, and an unwavering belief that his vision of a more productive, developed Tanzania is not just a pipe dream. This humility has humbled me. And for all that and more, this is an unfinished story that needs to be heard.

Escaping Conversations Not Worth Having

I am running out of patience for conversations that aren’t either humorous or sensible. Darker the humour, the better. The more truth plus humility plus sophistication, the more engaging.

But we prefer gossiping. This psychologist has argued that 80% of average conversations consist of gossip. It’s apparently “essential” for humanity.

Some other research says that we spend 60% of our conversations talking about ourselves. This doesn’t overlap well with the gossip stat unless we are gossiping about how everything screws us over. I, me, MINE.

Another study says that 60% of us lie at least once during a 10-minute conversation. And ooh, this bit is great – men generally lie to make themselves come off better whereas women generally lie to make the other person feel better.

I know all this sounds condescending. I am not, by any means, a 100% innocent here, but I am trying to beat those damn percentages.

A good friend preached not-so-long-ago that he refuses to have a touchy conversation without having a decent understanding of the opposing viewpoint. Let’s take guns for example. He, the friend, is anti-gun. So according to his sermon, he will only debate with a gun aficionado after understanding the depths of the pro-gun argument. He says Anish, I get livid when the other side doesn’t understand my perspective, so it’s only fair if I give their perspective a go.

Ever since the friend preached this to me, I have become a pious follower. Sadly, the majority haven’t yet been converted.

There is also the case of sensitivity. If you haven’t read Lukianoff & Haidt’s the Coddling, get on it already. They studiously claim that we, especially them Gen-Zs, are getting overly sensitive to being offended. Being offended is not the same as intentional bigotry. The charity of intention must be given to the speaker, at least in the beginning. This quote from their book summarizes this issue that is especially rampant on college campuses in developed countries:

The number of efforts to “disinvite” speakers from giving talks on campus has increased in the last few years; such efforts are often justified by the claim that the speaker in question will cause harm to students. But discomfort is not danger. Students, professors, and administrators should understand the concept of antifragility and keep in mind Hanna Holborn Gray’s principle: “Education should not be intended to make people comfortable; it is meant to make them think.”

A version of this happened to me recently.

A well-meaning friend asked me for feedback, and I was coy. She poked, come on Anish, let it rip. So, I gave her an objective observation as feedback. She seemed to have taken it well then.

A week later, I realize she has stopped talking to me. I had no idea what was wrong. When I inquired, she said you crushed my work that took months of sweat and emotional turmoil to put together. I reminded her that (a) she double asked for the feedback and (b) the feedback was an objective observation, NOT some random “it sucks because I don’t like it and I can’t tell you why.” To be fair, she apologized. But will I go there again? Cautiously, if at all.

Then, there is the hey let me bring up the exception to this argument and use it to debunk it completely. John smoked marijuana and ended up in the hospital possessed by a satanic version of Joseph. Thus, marijuana is evil for everyone. Never mind that this is an exception. An exception that proves the rule, maybe. Please don’t abuse an exception. More importantly, please don't solve for the exception.

There is also the hypocritical aspiration that humans should be perfect and if they make one mistake, irrespective of its magnitude, everything else is irrelevant.

Musk is a great example here. He’s divisive and I honestly don’t know why. Yes, he should watch his Twitter-fingers, be careful who he calls a pedo and be less of a dick as a boss. But, to use that to make him a villain while he is almost single-handedly trying (and succeeding) to save the Earth doesn’t make sense. Yes, he’s not perfect and you don’t have to be okay with his missteps, but to brand him as an asshole is to discount the exponentially more good he is doing than the average good person. Please have a holistic perspective.

Related to this is the illusion that you know more than you do, and then spend the next two hours arguing about something you know little about. Especially without the humility or awareness that you might not know enough.

I fall in this trap often. Sometimes as the guy who thinks he knows more, but more often as the bemused guy who ends up trying to have a conversation with someone who isn’t really informed or looking to concede to the facts.

Our big fat egos get in the way. And if your big fat ego continues freestyling without conceding to your own self-awareness of your big fat ego, then, well.

Also, Nassim Taleb once tweeted:

Never complain about people, no matter how justified. Just drive them to complain about you.

This whole post seems like one giant complaint. And maybe it is. Or maybe it’s a largely accurate observation. You're free to complain about it.

But the point is, we talk largely about ourselves, mainly gossiping; lying more than just occasionally while arguing against something we don’t fully understand, only to get offended rather quickly, setting double standards as we get swayed by the exception while also imagining we know more than we actually do, and then letting our egos get in the way even when we realize we are wrong.

Why have conversations at all then?

I am not saying I am fully innocent here. I am not. And I know plenty of folks who are capable of great conversations. And I love having conversations with them.

My quarrel is with myself.

When I encounter a sorry conversation, instead of hitting the escape button, I yearn to “knock sense” into the senseless. There is where I fall. I can’t let go. And then my emotions get in the way and I become what I have been berating. Especially when someone is irrationally trampling on grounds I am seasoned in.

Instead, what I need to do is disconnect. I am no preacher, no atheist missionary. I don’t have to enlighten everyone or get my point across every time. I just need to let go.

It’s time to create a new if-then loop. If person X is generally well-read, humble, gives the charity of intention and is open to reaching some sort of a compromised resolution, then continue the conversation, else person X is an annoying fuck and stop the conversation immediately.

This way, I’ll hopefully save some anxiety, however hard it might initially be. Maybe a good way to pull the plug is to throw in an insensitive, dark joke that effervesces the sanity of the poor victim. Deserved.

Round 2: Kenya

Hello Nairobi! Hold on, let’s back up for a second.

For the good or the bad, I am a planner. Almost two years ago, I grew a pair and quit corporate, conventional life. To justify it, I needed a plan – some direction, some inkling of a purpose to twinkle through. I dug deep and came up with a “big” goal that I scribbled down in pen – buzzword disclaimer: I will dedicate the rest of my life to fighting multidimensional poverty through economic empowerment, leveraging first the power of social enterprise. It sounds all flowery, cliched and dandy, but it’s something that has stuck for the last two years. And that’s been powerful.

I had my “big” goal written in pen, and now I needed a bunch of smaller goals written in pencil that would contribute in some way to this mother of all goals. There were a few options I was contemplating – (1) just go to India and start a social enterprise, (2) do your MBA with a focus on social innovation or (3) educate yourself by working around the world in the social impact space.

The India option was a direct, hail-Mary-esque route. Entrepreneurs are generally impatient and joyfully jump into the deep end without a life jacket, so this was tempting. But I did not want to be this slimy know-it-all hotshot who quit New York to start something in India, pretending to know everything.

The MBA was tempting for reasons of glory. An MBA from a top school establishes your ethos instantly, apart from exponentially feeding your already-bloated ego. My mentor probably gave me one of the best pieces of advice on this – do an MBA if you genuinely need it to achieve your goals. Intelligent people are the masters of justifying almost anything. And it’s dangerous because these arguments can be powerful enough to justify delusion. I didn’t want to delude myself – I didn’t need an MBA to conquer my goals.

To be clear, I didn’t default to option 3. Educating myself by working across the globe had always been my preferred option. The other choices had to be considered though if I was going to be logical about this. So, I considered those glorified options and dumped them, deciding to create my own custom, cheaper global volunteer-based “MBA”. I would spend six months working in Latin America, six months in Africa, six months in Southeast Asia, six months in India, and then settle in somewhere in Maharashtra to ignite my social enterprise there. All the “working” would obviously be connected to social impact.

My first hurrah turned out to be Guatemala. I was to spend six months there working for a social enterprise accelerator. The six months suddenly turned to fifteen. And my ambitious custom six-month rotational “MBA” went caput. But that’s the beauty of it. It made sense to spend the extra time in Guatemala. After six months, I had just about established myself. The unpaid fellowship soon became a decently paid job, and I got a chance to really add value while learning more than I could have imagined. Option three gave me reasonable flexibility.

The big goal had still not changed. But, it was clearly time to just adjust the smaller goals a little. Southeast Asia was out. Africa still needed to happen, but I couldn’t afford another fifteen-month stint, at least in my head. Enter Amani Institute. The program that they offer serendipitously landed in my inbox — it was like magic straight out of the wand of J.K. Rowling. This program is a 9-month certificate in Social Innovation Management, but more importantly, it involves a 4-month apprenticeship with a local social enterprise. They believe in learning by doing, and all this had me taking my shirt off and running around yelling hallelujah. I got in, secured an apprenticeship with Livelyhoods, and here I am in Nairobi.

This is my Round 2. In Round 1, I worked with a bunch of social entrepreneurs working in all kinds of cause areas. The breadth was what I wanted but we didn’t go deep enough. In Round 2, I will be working with one enterprise that is trying to fight poverty through job creation, sublimely aligned with what I want to eventually do in India. Add some theory on communication, leadership and management, a network of like-minded but diverse professionals, and I am all giddy right now. The program starts tomorrow. The first week is a quick crash course on biomimicry. We are going on a retreat in the middle of nowhere in Kenya to introspect and connect. Cliched, I know but I love it when you experience why clichés are clichés.

I found out about this while I was in the middle of Bolivia. I still had a month of travel left. I was about to see Colombia and parts of Guatemala that I hadn’t yet. But all the while, I couldn’t wait for tomorrow, for the start of this next round. I feel so spoilt. There I was, travelling the world, but all I could think of was getting to Nairobi to start my apprenticeship. That’s what is so powerful about direction. “Work” becomes play, and conventional pleasures become unwanted distractions.

Find your big goal. And make it happen. It doesn’t get better than that.

Harari-chal Earthquakes

I finished Homo Deus a week or so ago, and just wanted more Harari in my life. And I got more Harari in my life. Enter 21 Lessons for the 21st Century. And it was a mind-numbing, questioning-everything 100,000-foot skydive that capsulated an explosion of knowledge, thought and re-evaluation. Anyone who really wants to understand what we Sapiens are dealing with today should read this book. I.e. everyone.

When reading Harari, there are two contrasting feelings that engulf the trenches of the biochemical reactions in my head:

1) Sensual history word-porn can't stop

2) Constant existential crises

#2 haunted me multiple times. Constantly.

Harari states clearly that his predictions are intentionally more negative as it's important to prepare for the not-so-dandy possibilities of the future. He narrows this down to three global challenges - technological disruption, ecological damage and risk of nuclear obliteration. He explains all of this with brutal, truth-based logical explanations that are hard to disprove unless you strawman them. And strawman-ing is for chums. Steelman him all you want and please invite me to the party.

Besides the future, he also touches on all the key aspects embroiling and polarizing our society today - immigration, terrorism, fake news, education, meaning, nationalism, data and fourteen such other existential battles. My attempt to summarize any of those will definitely be a fool's errand.

So I won't. Instead, I'll talk about my "feelings" towards it.

There is so much knowledge in this book. So many ideas, thoughts, considerations that few have the intellect to imagine let alone the courage to say. In parts, I felt stupid, because of so many "obviously-how-did-I-not-think-of-that?" moments on community and education. In parts, the book validated some of my thoughts on meaning, religion and data. In parts, the book explained things that didn't make sense before such as the psychology behind immigration, ignorance, and basic Sapiens instincts. In parts, the book created notions that I probably never would have even thought of imagining, such as his takes on culture and post-truth.

We are no longer racists, but we are culturalists, and that can be as dangerous because it's more aligned with our current moral construct. We need fiction and have needed fiction to survive, even while we chase truth. The systems and the society we have are too complicated for an individual to understand so kill all those crazy conspiracy theories. Superhumans will happen.

All of that might just seem like random statements, but Harari chisels it out with such flair; combining history, stories and ideas in the surreal adventure that this book is.

What really rattled me was his concrete belief of the destruction of our utility. Most jobs will be automated away sooner rather than later, and this time, it will be different to what happened in the industrial revolution. Why? Because last time, machines freed Sapiens from physical tasks, leaving room for us to dominate cognitively. AI and Machine Learning will take over our cognitive abilities, and there is no third value-add skill that we possess. Then what?

This is personal because I want to spend the rest of my life fighting multi-dimensional poverty through economic empowerment, which basically means job-creation. It wasn't like I was unaware of the threat of AI before, but Harari made it a lot more real and inevitable. Not through fables, but through logic. And logic is a strength I pride myself in, which in this case, for a split-second, felt like a weakness.

But knowing is more important than living in ignorance. Thankfully, Harari agrees with me on this. And now I know. This doesn't change my goal of fighting poverty through economic empowerment, it just makes it harder. Job-creation is and was one way of doing it, but there are others. Sapiens will always need and want purpose, dignity, economic independence and community. We will just have to come up with different ways to attain them whilst our ecological haven crumbles and Homo Deus contemplate the genocide of us Sapiens.

Read Harari. Read all of it. Read it again. And then again.

Traveling Is Dead. Get Immersed And Contribute.

Tourism was dead ages ago. Travelling is dying, if not already dead. What’s in right now is contributive immersion. Here me out.

I have two months before my next stop. Thought I would take advantage and travel a little. But, a different kind of travel. Less about seeing, more about being in my head. Less about meeting people, more about reading, writing and thinking. Less about experiencing, more about retrospection. Or something like that.

There was this other weird feeling I was battling before I started this two-month “adventure”. I wasn’t that excited. Here I was, with two months of freedom to travel to wherever I wanted. This luxury that most people crave. This bundle of time that not many people have. And look how spoilt I am. I am not even excited.

Excited or not, I was doing this. I started in Holbox. This quaint, secluded island in the north-east nothingness of Mexico. I remember a random Mexican entrepreneur had mentioned it to me way back in 2017, and it stuck. Aside from the usual commentary of it having stunning beaches and tranquillity, it was also supposed to be Mexico’s best-kept secret. At least back then. Now it’s probably Mexico’s “best” kept secret – in quotes, with a winky face right next to it.

There is this steaming irony while being a tourist. A hypocrisy of sorts. I, a tourist, want to travel to a place where there are no other tourists. I, me, MINE and no one else. Besides my friends, of course. And some local people who I can somewhat communicate with. You know, to get a “local” experience.

Holbox is now infested with tourists. I took a local bus from downtown Cancun to get there. When I got to the bus station, I was wondering which gate I had to be at. So, I did what most tourists would do. I looked for a gate with a line of tourists. And there they were, like a bright orange buoy in a sea of locals. Backpacks, flipflops, an air of superiority and yes, I fit right in. They were also going to Mexico’s “best” kept secret. Obviously. Comforting. Easy.

Holbox is stunning. With or without tourists, the beaches are pristine. The water, as blue as turquoise. No cars, only golf carts. No real roads. Tiny. Hammocks in the middle of the ocean. Bioluminescent plankton sparkling in the blackness of the night sky. Birds, crocodiles (saw three of these salt-water beasts), mosquitos, flamingos. Sandbars stretching into what seems like the middle of the ocean. Sunsets as pure as the painting of a ten-year-old – cloudless, round, perfect.

And then there is capitalism. Opulent hotels, customized tours, yoga (of course), a lot of tourists, a lot of UTL (Universal Travelling Language / English). People travelling in twos, threes, fours. Folks from literally all over the world speaking tongues hard to decipher, bonding over how accents make things sound funny. “How are the beaches?” Beaches are sometimes mispronounced in translation as “bitches” because “e” = “i” in Latin languages, etc. Queue a plethora of pun-tastic jokes, especially among the men. “The beaches in Holbox aren’t as fun as the beaches in Cancun.” Ha. Ha. Crude. But funny. A good way to bond, apparently.

I heard the same pun-ny jokes in Costa Rica. “The beaches here are so beautiful.” After five days in Holbox; reading, thinking, observing and not making friends, I made my way to San Jose. I was done with beaches and wanted some hiking, mountains, forests, waterfalls. Waterfalls. Waterfalls are special. Yes, go chase them waterfalls if you can.

A friend of mine was travelling in Costa Rica as well. Isolated with all this isolation, I thought I’d join him for a couple of days. He was “Twaling.” It’s apparently this new concept where you travel with a local. So, we had Adrian, our local, taking us around. He wasn’t really our guide. He was like an acquaintance who quickly became our friend. He took us to places he found cool, sometimes off the beaten tourist-y path, and sometimes on it. In a short five days, we got more of a local vibe then we would have if we did things ourselves. We rappelled down waterfalls not infested by tourists. We saw a giant seven-hundred-year-old tree of peace, leaf-cutter ants, sloths, scorpions, armadillos, monkeys, spiders, snakes. We stopped in the middle of nowhere to drink coconut water and sugarcane juice without fear. We sat alone in natural, volcanic hot springs in darkness lit only by the candles that Adrian had strategically placed. Yes, an upgrade. But how long can you get a local to just show you around?

Costa Rica is a spectacular mass of land with everything you can imagine. It is a well-run country that decided ages ago to get rid of its army and invest this extra money into education. So, you genuinely sense a general level of development across the board. Almost all of Costa Rica (~98% apparently) is run on renewable energy – hydro, wind, solar. The government also thought it would make sense to invest in making tap water drinkable. Sounds expensive but apparently the medical costs you save from reduced water-borne diseases very much offset the extra cost of purifying water. Plus, it is just a good thing that Governments should do. And, like any intelligent Government, Costa Rica also decided to make the most of the tourism potential that nature had blessed it with.

So somewhat like Holbox, Costa Rica boasts a string of fancy hotels, natural reserves, hanging bridges, ziplines, a lot of tourists, a lot of UTL and typical touristy inflation – shit’s expensive. They also go the extra mile by making things as eco-friendly as possible. “This is an eco-friendly wildlife reserve with a perfectly constructed hiking trail, spotted with comfortable benches every hundred meters to rest, and we are working on making the hiking path wide enough to meet global accessibility standards for the less fortunate.”

All this is awesome, but where has the rawness of brute travel gone? Yes, I get to see pretty things and do safe, fun activities, without any communication issues thanks to UTL, but am I really immersing myself into the culture and the nature that a foreign country offers? Why go there at all? What am I even looking for when I go to a new country?

That’s the crux. What are you looking for when you go somewhere? If you’re looking for an escape, a place to recharge, then being a perfect tourist in a comfortable, touristy place is great, and power to you. If you’re keeping a count of all the countries you have visited, and the number of likes your Instagram posts get, let’s not be friends but do what you need to do.

You could also be a pitiful inbetweener. Someone who wants to genuinely travel and see and absorb and experience, but just doesn’t have the time, the budget or the passport to do so. All you can afford is a couple of weeks a year, imprisoned by your lucrative corporate carcel. Then, you can’t help but plan out every hour of every day, making the most of the limited time you have, and doing all the “touristy” stuff because not only is it easy, it is also rationally your best bet. Unfortunately, despite your traveller instincts, you can’t help but be a tourist. I get that. I was in that prison.

And then you have the gap-yearers. The “true” travellers. 365 days of travelling the world, or a continent or a bunch of countries. The freedom to not really plan things out, to take it as it comes. To fall in love and then just stick around. To live in hostels and yachts. To get wasted and then get laid. To take surf-lessons and salsa classes. To teach UTL or bartend to earn a bit of dough. To experience the world. To get “out of your comfort zone”. To be interesting. To have stories to tell.

One of the most uninteresting things is someone who wants to be interesting.

To me, all of that is not the essence of going to a new place. You can recharge in a fancy hotel down the road. If you want to rack up the number of countries you have visited to prove how “worldly” you are, why even bother spending more than a day or two in a country – just go to the capital city, take a dump at the airport, and then fly to the next capital city. Simple, and you’ve even laid your mark. I just feel sorry for the inbetweeners. I have been there, and it sucks, but honestly it isn’t hard nowadays to break out of your prison. Gap-years are better than two-week affairs but frolicking around from country to country for a couple of months at a time gives you only a flavour of the place. Tastes can be deceptive; an entire meal is what you should be looking for. And, many-a-time you get stuck with other gap-yearers like you, or with locals who are only friends with foreigners. It’s a deceptive little bubble. A bubble that a part of you wants to burst out of and a part of you wants to stay in.

Ugh, why the negativity, Anish? What do you want, why is travelling dead?

If you really want to see, understand, experience, learn and grow from a foreign culture, you must immerse yourself for a significant period. At least six months. Only in one city or town or village. And you have to be contributing there. Adding value in exchange for imbibing localness. That is immersion.

In the past, long-term travelling gave you this. But today, travelling around and just “being” is contaminated by the tourism industry. There are so many people travelling, being tourists and taking country-hopping gap-years that if you enter a country and bartend at a hostel, you’re barely getting out of your comfort zone. You’re still in that little bubble with just enough moral license to convince yourself that this little bubble is where I should be. When in fact, you’re better off bursting out of it. That’s why travelling is dead.

I lived and worked in Guatemala for fifteen months. It started with a six-month fellowship where I was leveraging my finance skills to help local entrepreneurs out. I ended up getting hired by the company and really immersing myself in the heart of Guatemala.

And no, it wasn’t perfect. Being a foreigner, I surrounded myself with enough foreigners conversing in UTL. Some of my closest friends were not locals. As much as I was aware that I did not want to be in a bubble, I sometimes was.

The saving grace was the work I was doing there - my contribution. For a majority of my time there, I was working with locals, supporting local entrepreneurs, understanding the local landscape of social impact, and living the local life. That’s what made the difference. That is where the learning, the growth and the cultural exchange happened.

And it wasn’t always fun. Learning a new language is hard. Cultural differences can be frustrating. Homesickness is always a thing. But that’s the point. No good movie, no good story, no good experience is a 100% positive.

So here I am in San Jose, Costa Rica, trying to travel for a couple of months, and I am barely excited. Some sort of societal pressure has made me want to travel and see things the old school, dead way. A part of me feels like I have earned it after the intense fifteen-month stint in Guatemala. But the truth is, once you experience true contributive immersion, old school travelling is just not the same. Tourism is even more of a joke. My sister felt this after her three-year stint in Spain, and I’m feeling it now too. But I am still going to continue. Yes, shut up, I know. I’m friggin’ human, unfortunately.

I’m glad you’ve made it this far in this long, gloomy post. I am not saying that you should never travel or never be a tourist. I am not anti-travel. Something is better than nothing, so even if you have a couple of days to get out to a new world, do it. Travel. Tour. Recharge. Experience. See.

What I am trying to say is that there is something far better out there. And it has never been easier to do it (sabbaticals, gig economy, the friggin’ internet). If you want a true, deep, pivotal, worldly experience; find a city, commit to it for at least six months, immerse yourself and contribute. And then, experience the magic.

Oh Guatemala, Thank You

Fifteen months. I was supposed to stay there for six. This was my first hurrah outside of “conventional” life, outside of society’s prescribed path to success, and my first hike down this new-found path has been everything I hoped for. And, I am not just saying that to adorn an average experience with fake pearls of positivity – it was not all fun. In fact, it was hard, and challenging and refreshing and exhilarating – in parts, and all at the same time. It was exactly what I had signed up.

Learning a new language is hard – not just to get by, but to actually work in. I arrived in Guatemala almost dumb and deaf, hoping to somehow make an impact and learn at the same time. It’s difficult to add and gain value when you can’t communicate - that was the first mountain I needed to climb. But there were enough folks who spoke English, so I got by and it wasn’t all doomsday. And, the people at work and in the city never made me feel unable or uncomfortable. The support and the patience up this mountain have been humbling. In the end, I don’t think I ever summitted this Everest of proficiency in a new language, but I did come to terms with it, hitting a gear of fluidity that I was somewhat okay with.

There is something beautiful and thoroughly engaging about going to “work” to do exactly what you want to do – not for money, pride, status or power. Alterna, this non-profit that supports entrepreneurs of all sorts in and around Guatemala, gave me exactly that. I was a “Fellow” there to start off with, and soon embedded myself into their DNA, giving blood, sweat and tears as we shook things up. We not only re-branded externally, but we hit the reset button internally as well, emerging afresh. We served over 150 entrepreneurs in 2018 in some form or the other. Our signature event is a five-day workshop where twenty of our more advanced entrepreneurs go through a topsy-turvy journey – from questioning the existence of their businesses to embracing strategies that can exponentially grow their sales and impact. Imagine that, twenty entrepreneurs in one room, sizzling with infectious ideas and ambitious personalities, and us trying to rattle them. The vibe that the space has when all these atoms of energy collide is magical.

I will never forget the feeling after our first, re-thought workshop. All the effort, the fighting, the disagreements, the uncertainty and the moments of discomfort were worth it. We came out flying. Our entrepreneurs were overwhelmed with action-plans, introspection and gratitude. And for a hot second, we, the tribe of Alterna, could reflect. The inner explosion of accomplishment, contentment and pride that I felt that day was so pure, so real. It wasn’t about the money – I wasn’t making any nor did the entrepreneurs pay for this workshop. It was purely about the value that we had added, without any sort of ulterior motives and with only the success of our entrepreneurs in our mind. This feeling, the purity of it, is so important for my overtly rational self. In my five years of hustle in Corporate America, I had never felt this way.

It wasn’t all hunky-dory though. My love-affair with Alterna meant that I was invested – heart, soul and mind. And when you’re invested, your expectations sky-rocket. Some days were hard. Everything takes time, but everything takes a little bit more time in the non-profit world, and I was constantly battling my impatience. I was living a lot of what I had read about when it comes to the difficulties of the non-profit space – a lack of resources, a lack of investment in and on talent, living more or less at the mercy of our sponsors. It was daunting and frustrating, sometimes just like any other job, but this frustration came from the desire to make things better. It is so important to be bothered and frustrated because that’s what helps generate change. I think living is a lot about learning how to positively channel change out of things that genuinely bother you.

One thing that the non-profit space has in abundance is passion. That is sometimes the best part about it. But anything in excess is not necessarily good, right? How can we balance the passion of this space with a higher degree of result-centric rationality? When does passion become a moral license to do just enough to internally satisfy yourself, while not really changing the status quo? I have been thinking a lot about what comes in the way of progress, both internally within myself, and externally when it comes to this space.

Externally, how can we change this moral expectation of demanding extreme sanctity from folks working in the social impact space? Why can’t professionals in this space make good salaries, earn good bonuses for dedicating their life to a cause, and even make mistakes along the journey? How do we start changing that mindset? That’s why social enterprise makes so much sense. Social enterprise adds another dimension to traditional business by roping in morality, because morality is tied closely to what impact truly is. So, if we can combine the fruits of capitalistic business models with the morality of the impact space, holding the latter as the true driving force while keeping the cause as incorruptible as possible, I think we have a real chance at true, scalable impact. I want to embody this and find folks that are aligned.

Internally, I have been battling the idea of patience – what is patience? And how do you find the balance between patience enabling mediocrity versus impatience coming in the way of excellence? It is all about managing expectations, and it’s all about finding the right balance. But what is this “right” balance? I need more practice at practicing that.

It was the hardest when Alterna had won my heart over. I always knew I couldn’t commit myself to Alterna for a longer period, but when you’re invested, it’s that much harder to come to terms with it. Towards the end, it was like the nails were inching closer and closer. My duty was not to do but to empower, to leave behind as much value as I could, without really creating severe dependencies. I am a doer, so this was hard. But I need to be better at empowering, and all this was a lesson at that. My long-term goals lie in India – I will work on poverty alleviation through economic empowerment there. It makes the most amount of sense in terms of the impact I can make for a multitude of rational reasons, and that is and has to be the only way I should be making key decisions. Initially, I wrestled with the idea of starting something right away in India versus taking my time and learning along the way with experiences outside of India. The winner could not be clearer. The amount I have learnt about starting and running a social enterprise without investing any significant actual and emotional resources is incredible. I am so much smarter now, learning from the mistakes and successes of other social entrepreneurs without any self-serving bias that embroils them. The best way to learn is by doing, by embedding yourself not in case studies, but in what is real and could eventually become a case study. There are no formulaic “right” or “wrong” answers. Textbooks are guides for what works in general, but it is important to not be trapped by their rigidity. So, one more stop on this magical school bus and then here I come, India.

Guatemala, to me, was not about the volcanoes, the lakes, the crime or the people, it was about what I was doing there. Yes, the people around me were beautiful inside and out, with those volcanoes constantly exploding my sense of self, and the lake, absolutely stunning. But what defined my time there were the entrepreneurs I worked for and the colleagues I worked with. Everything else was icing on the cake. This icing was delicious though – I met some incredible people, breathed in volcanic air, jumped into the lake letting myself go to the all the Mayan beauty that for once didn’t have to revolve around rationality, saw bravery and struggle, learnt how to shut out love, never got robbed but sympathized with those that did, understood that it is important to have standards for yourself and the people around you, but it is also important to not project your ambition onto those who are not wired like you, cried a river embracing the joys and pains of work, life and introspection, felt more alone than ever and also more accompanied than most, earned more self-respect, laughed a lot, learnt a lot more, gave, got and cherished.

For all that and more, thank you.