Excerpts From Sangamner

Thursday, March 5th, 2020–1:23pm, Sangamner, India.

All kinds of humbled right now.

It is my second day here in Sangamner, and it feels like so much has already happened. I have been in India for over two months now and it’s been a little surreal, a little slow, a little lost, a little uncertain. I have been a little sick throughout, and it feels like a little bit of a lot of the world is falling ill along with me as the Corona Virus sweeps fear across the masses. It’s all a bit strange right now in the world, and yet somehow, all I can find is a little bit of optimism.

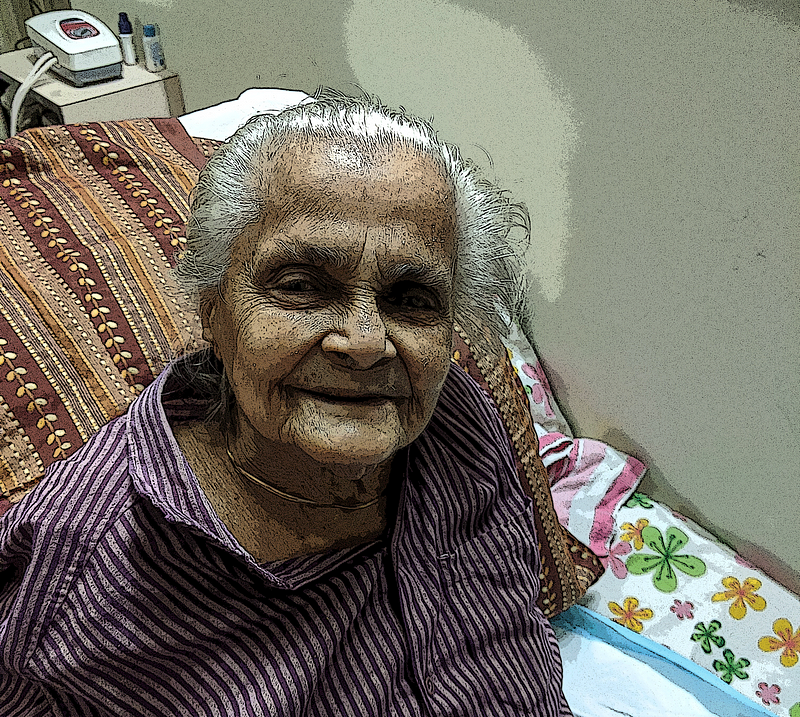

My ninety-three-year-old grandma is lying in front me. She is moaning softly, meekly, sporadically. She can barely move. It’s like she is crying to herself, but she yearns God. It seems like she is taking God’s name in vain, but the truth is, she is taking God’s name with a sense of futility that only death beckons. She has seen better days.

Yesterday, she fell off her bed. She had been doing better, and all it took was a lapse in judgment, a moment of over-confidence, and she came crashing down. I wasn’t there, but I was told. She fell onto her nightly helper, who also hurt herself. My grandma has gotten a bit heavy — too many laddoos that almost seem like compensation for her dearth of joy, the lack of purpose that old age brings.

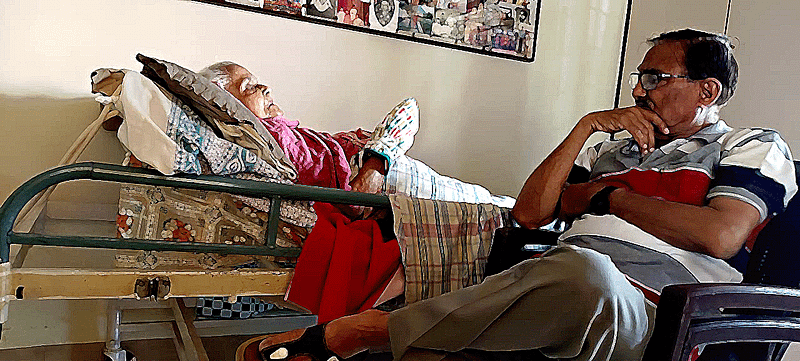

My eldest uncle and aunt, Babaji and Maa, are God-sent. A different breed with a different, elevated level of integrity that would humble even the wisest. As I grow old, I am learning that wisdom, more often than not, lies in action, not in words.

They were supposed to be going to Kenya to enjoy the wilderness of where it all began. But the fear amassed among the people of the world cancelled their escape. The Corona Virus might be only as dangerous as the common flu, but the fear of the unknown that it elicits has already brought the world to its knees. And it’s only the beginning. It’s as if one of our greatest unifiers, fear, might also be our greatest downfall. Or a just a brutal reset as prescribed by the scathed mother nature.

The disease didn’t scare away Babaji and Maa. Babaji said to me — death is certain, it’ll find us whether we are in Kenya or not. But instead, societal norms shackled their will. The couple they were supposed to go with buckled under pressure and Babaji and Maa caved into having their trip postponed. I urged them to go without the other couple — everything was already booked and paid for — but they said quietly, “Aise nahi hota hain” — this is not how it works. That’s how India is sometimes — culture becomes reason.

And just when their trip was getting cancelled, my grandma fell. It seemed like a sign, and it was enough to rationalize that they had to stay.

My grandma doesn’t fully recognize me anymore. I am a familiar face at best, and my name, a lost memory, confused constantly with another cousin. But it doesn’t matter. Nothing really matters to her anymore and not as a function of her arrogance, but as a function of her pain. Of boredom. Of an inability to contribute. It’s like she is looking for peace and is starting to realize that only the end will bring it to her.

It’s such a stark scene. My grandma, the pillar of our family always standing strong, the woman who worked three jobs to give her children a chance to succeed, is now reduced to a weaker version, humbled by the humanity that science explains — everything depreciates. Almost on cue, she turns to me and says, “Where do I go from here?”

My grandma is in pain. She can’t really move, and is stuck in bed all day, all the while her body and her mind yearns to move and do and be. She hates that we have to take care of her. She hates that she wears a diaper. She asks me if she is bothering me because I have to look over her at times — “is this why you came here?”

Is it even worth it anymore for her? She’s 93. Lived a whole-hearted life, filled with love and growth and accomplishment. Now this dementia, this pain, just seems like throwing the shit she sometimes sleeps in on a beautiful painting she spent all her life drawing. Why ruin it at all in the end?

Old age sucks.

Friday, March 6th, 2020–6:44pm, Sangamner, India.

I wanted to write more yesterday.

Sangamner is different this time around. Not because it has changed, but for once, I have come here with a different lens, a different purpose — not just to visit family and “tolerate” the backwardness of suburban India, but to imbibe what it means to live here. As Dad says, everything is research for me right now. And just like that, everything is different for me even though it’s all the just the same.

Yesterday, it was my Maa’s birthday. On an average day, she is neck-deep busy, advocating for the rights of her clients, taking care of my grandma, and the tens of other things she does. She wakes up at 5 in the morning, leads a two hour session of Yoga for some of the older women of the town, marshals the troops at home afterwards, goes to court, comes back for lunch, goes to court again, comes back for an early dinner, feeds my grandma if she can, goes back to court, comes back, runs errands and then goes to sleep around 11 at night. It all starts again the next morning at 5. This has been in play for the last forty odd years. And yesterday was her birthday.

Her birthday almost made her phone sound like a thriving call centre. It kept ringing with the joy of well wishes. People kept coming over — so many with so much love. There was so much love that quite literally, it was stressing Maa out. It was a testament to the work she does for her community. And it was a testament to how suburban life in India is. Together. Happy.

The door of our house in Sangamner is only locked at night. Or rather, it’s almost always open. People come and go, with and without a heads up, refusing with effusing amounts of politeness any offering but realizing that they must take something sweet or salty, because that’s what they would have done too. There’s respect, admiration and love, and it doesn’t seem fake. It’s born out of being there for each other, and those that give more, get more of it. My Maa and Babaji give with all their heart.

I feel like I have been blinded all this while. I always wondered why Babaji didn’t leave Sangamner for “greener pastures” only to now realize that he already has the greenest. Money really isn’t it. It’s community. And I know this sounds cliched, but when you see it glaring in your face, and the happiness and self-worth it embodies among the people it embraces, you can’t help but be humbled.

Dubai, Bombay, Pune, the urban West, are just not the same, at least the bits I have seen. I lived three years in New York and never met a neighbour let alone got to know them, and I was by no means the exception, I was very much the rule. Relationships are superficial, driven by things like kids sharing the same age and the same nursery, so their parents become required friends. The nuclear family rules, while driving children into depression, as the illusion of chasing money and comfort denies them their innate hunger to be social animals. And social animals not just with a few, but with many – similar in ways, in thought, in history, in culture. It’s the most intelligent that seem the most brainwashed.

Look, I am fortunate to be preaching this. I was blessed to not have to worry about money, and there’s a luxury there that lets you free your mind. And obviously, all those that have money aren’t depressed — they live decent lives, maybe burying their discomfort in delusion, but it can still be worthy. Rather, what I find compelling is how have we have built a society that revolves around money rather than well-being. Money was an important invention, but did greed win? How do we teach our kids to chase purpose and belonging instead? Why does it seem like going abroad is where the gold is? How did we get our basics wrong? Dopamine is the devil.

I started driving classes here because driving in India is like driving in a different world. The horns, the lights, the people have different rules. The driving class isn’t very helpful — it starts late, I only get fifteen minutes because it’s a group class, and the instructor isn’t great. But I get an hour with four young men of Sangamner and how they tackle their lives there.

On my first day, one of them saw me walking back by myself. He stopped me in the middle of the road, and said aren’t you with the Malpani’s? I said yes, and he said, hop on my scooter and I’ll give you a ride. So, like any Sangmaneri would do, I hopped on to his little scooty and he dropped me off home. Now he will pick me up and drop me off every day. I asked Babaji what that was all about. And he said that he is their lawyer — “of course the kid knows who we are”.

That, in a nutshell is Sangmaner. Small. Together. Happy.

Comfort needs to be redefined.

1 Comment

Comments are closed.

👍👍😀